Building of Community-in-Resistance: Weapons of Mass Creation

In our world the ongoing commodification and neoliberal individualisation has long seeped into the very way of life, into our thinking and even acting. In order to resist the existing order, it has become urgent to counter the tide, to think and enact more collective forms of resistance and emancipation.[1] Within HKW’s New Alphabet School format, one possible trajectory is to rethink and return to revolutionary alphabetisation of the past – to return to those thin segments of victories of the “oppressed” that help us move beyond the melancholic seduction of defeat that the left has been holding onto.[2] Such travel to the past can become one important terrain to insist and persist in spite of catastrophic prognoses. This short contribution takes a journey into one of the darkest times of the twentieth century: fascist occupation of Yugoslavia, World War 2. It is worthwhile to consider that despite such impossible circumstances – no developed communication channels, no material base and infrastructure for antifascist resistance (no ammunition, no funding, no food) and an extremely high risk and threat to anyone that dared to think or act in resistance (immediate execution, tortures, camps) – that the genuine articulation of partisan art and politics emerged and contributed to a collective cultural and political form of resistance that was the base for community-in-resistance. New partisan forms of cultural production and dissemination became a veritable weapon in the struggle against fascism, and a weapon to create a new political subject/entity, what I named “weapon of mass creation”.[3] Is it possible to speak of weapons of mass creation one might ask, in times in which only weapons of mass destruction reigned supreme? Also aren’t partisan art and culture to be reduced only to a propagandistic function that disseminates what is decreed from above? My answer to this question is negative. I claim that there is a strong and long thread that connects various armed struggles, from antifascist to anticolonial, that share the dimension of arming people and culture with new significance in their collective fight and participate in the building of community from below (and not only from above).

Resistant bodies and minds of partisan men and women succeeded to form a collective body only when they articulated the symbolic means of resistance, the new imaginary, not only of fighting the fascist occupation, but to radically transform the existing order. In other words, partisans fought for a new world, one that they wanted to seize by making, experiencing, and creating it. This positive moment of “liberation” relates to the work of masses – and cannot be reduced to the work of established intellectuals, artists, or the communist vanguard party. The Communist Party of Yugoslavia was the most important force in the resistance, being made illegal in the early 1920s, it had experienced what it means to work from underground, despite however only having a very few members and weak material infrastructure. In other words, the resistance was a vivid infrastructure that relied on the collective participation of people that resisted, and all those that entered new political and cultural institutions on the liberated territories. This was a new constellation, and I claimed elsewhere that the unique hold-encounter between partisan art and politics yielded strong consequences.

During the liberation struggle more than 40,000 poems and songs were written in Yugoslavia, there were thousands of printed journals, weeklies-monthlies, thousands of graphic art, linoleum cuts, thousands of photographs[4], an impressive array of theater performances, novellas, symphonies, and even some films were produced. Again, this was an impossible partisan thinking-artistic-political machine that was relying on masses of often anonymous poets, performers, self-educated designers, and most of all the partisan capacity and improvisation. Masses were not only consuming partisan culture, but became an integral part of (self)educational and cultural process[5].

These practices were never self-enclosed into a system of elite partisan institutions and public, but have been consistently related to emancipation of the spectators[6], and more, towards breaking the border between those that produce and those that consume art. Also importantly, the new partisan aesthetic community was based on a productive combination: while some partisans used the existing popular and amateur artistic sources, eg. folkloric dance and songs, then there were those partisan artists that used most avangardist poetic and graphic formats. Furthermore, a typical cultural gathering entailed agit-prop sketches and performances, singing of vernacular and international(ist) poems, exhibiting of graphics, as well as theater performances and folk resistance dances. This dense combination of folkloric, popular and avant-gardist practices mixed with a magnitude of words and images of resistance actually produced the major effect, a collective tie of partisan community that further created new, federal, and socially just Yugoslavia. Juxtaposed to the old Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which was a semi-fascist dictatorship during the 1930s, new partisan Yugoslavia stood for equality of all nations and nationalities for a single, organised oppressed. The cultural work then cannot be seen without the relation to the general people’s liberation project, but also needs to be analysed in its interiority, i.e. how it gained its own autonomy, and unfolded alongside the physical weapons and strategies of military resistance, side by side the political building of partisan counter-institutions of mass democracy, and also beside the elementary organisation of partisan reproduction.

Partisan “monuments to revolution”: star, dance,…

Now despite, as is clear from above, the creation of a partisan community-in-resistance, this is a matter of a longer duration and complex encounter between different but equal activities (military, political, cultural). I will present a few artworks/practices that contributed to the creation of a partisan community. For contemporary research either theatre of liberation or diverse poems and songs[7] ( performed and still perform a very strong affective tie, weaving and building the community. In particular singing meant the coming together of the community. This performs and enacts the community itself even today, and if particularly strong, can function as a sort of “monument to revolution”, in the words of Deleuze and Guattari:

A monument does not commemorate or celebrate something that happened but confides to the ear of the future the persistent sensations that embody the event: the constantly renewed suffering of men and women, their re-created protestations, their constantly resumed struggle. Will this all be in vain because suffering is eternal and revolutions do not survive their victory? But the success of a revolution resides only in itself, precisely in the vibrations, clinches, and openings it gave to men and women at the moment of its making and that composes in itself a monument that is always in the process of becoming, like those tumuli to which each new traveler adds a stone. The victory of a revolution is immanent and consists in the new bonds it installs between people, even if these bonds last no longer. [8]

I would like to start with one of the most emblematic photos which became quite famous during and immediately after the Second World War. The photo displays and stages the most prominent symbol of the partisan struggle. We see how schoolchildren and their teacher from a partisan school form the five-pointed star. The photo was taken from a neighboring hill, thus one gets a semi bird’s-eye-perspective over the bodies creating a star.

It was a cold winter’s day in Babno Polje in 1944, when then emerging partisan photographer Edi Šelhaus asked the partisan teacher Nada to organise a small staging of a star with her pupils. The performance was carried out by the pupils from a partisan school and as Šelhaus recounts, German planes would often patrol the area. Thus, staying outside and displaying obvious political messages would not only have endangered lives, but also exposed the location of the local resistance. A few weeks later, the photo was published in various Allied newspapers. It seems that the idea to stage a star on a winter day was highly risky, yet at the same time did indeed capture the resilience of the partisan organisation. Schools that contributed to the Liberation Struggle, in their own way, were organised in the liberated territories. The image of a star in the middle of a field transcended the fear and was ingrained in people’s memory, staging the symbol of liberation and their community. Such partisan gestures and performances with the help of photography succeeded in staging a living monument to the community-in-resistance.

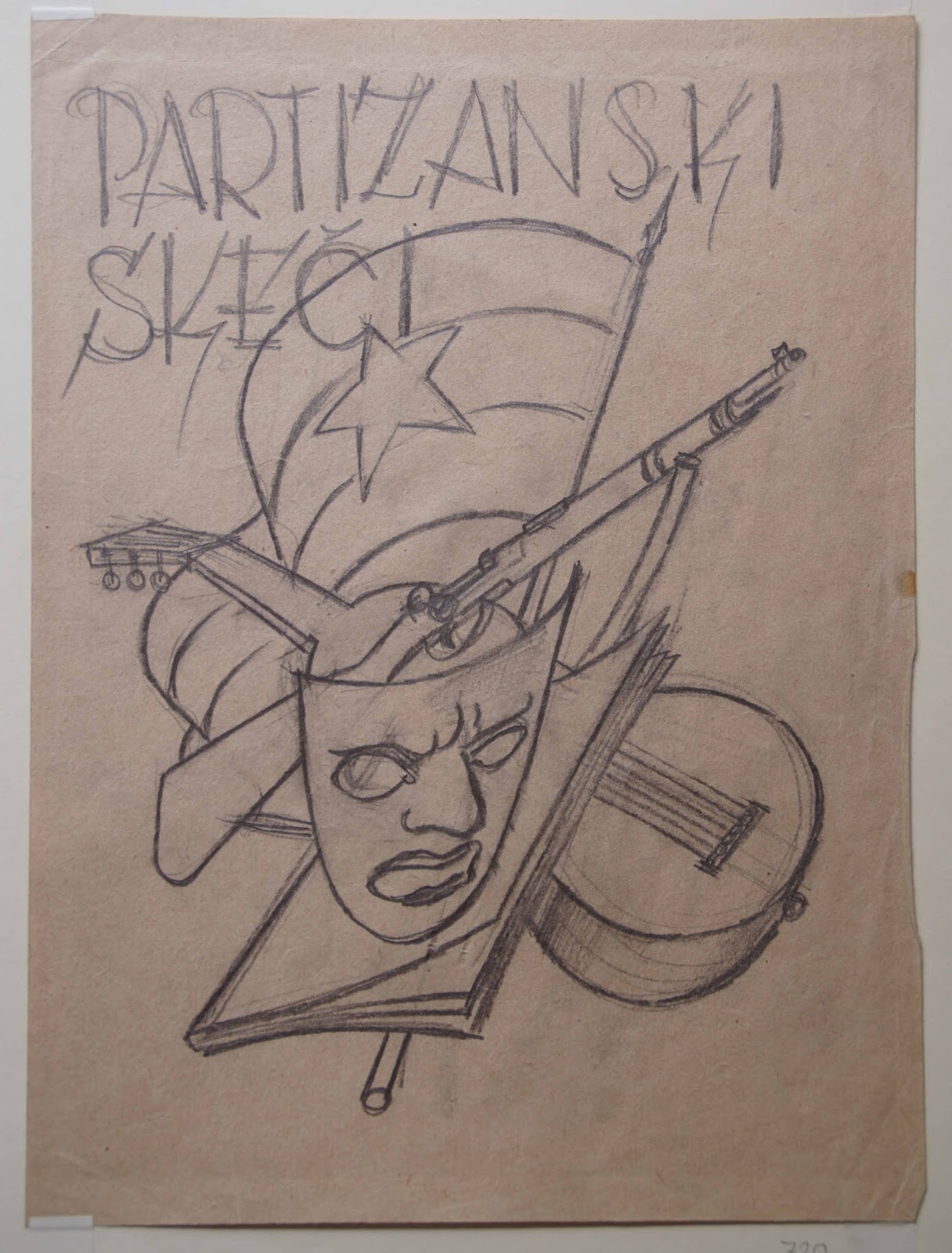

However, if a star represents a conventional imagery of revolutionary struggles then a drawing named “Partisan sketches” (image 3) goes on to emblematise the core of partisan activities and community. “Partisan sketches” is a work of Dore Klemenčič who was assigned a role in partisan propaganda. The drawing complicates the more generally expected and accepted canon of partisan figures: a star, Tito, a male or female fighter adorned with guns, smiling and at times carrying the star on the hat. The drawing represents the “community-in-resistance” by consisting of a fully armed and empowered partisan struggle. This drawing actually redefines the notion of a weapon in times of war: Alongside the obvious rifle we see a guitar, a theatre mask and a book that are assembled under the flag of the new Yugoslavia, which carries a star. Finally, the drawing expresses the equivalence of the different “arms” used in struggle and puts on display a deeper solidarity between political, cultural and military work that aims for liberation. This lucid transfiguration displaces the individual partisan figure onto the struggle itself that is consisted of plural and egalitarian activities.

I would like to end with one fascinating partisan dance of Marta Paulin-Brina,[9] who joined a partisan cultural group and was both engaged in the military and cultural struggle. She performed her dances on different occasions, but the photo and the most memorable experience took place on the day she was invited to perform at the inauguration of the Rab partisan brigade. The latter comprised of liberated survivors, among them hundreds of Jews of the concentration camp on the formerly Italian-occupied island of Rab. The event was fueled by the symbolism of homecoming and the struggle for freedom after the horrific experiences in the concentration camp.

Paulin-Brina struggled with the question of how to dance among partisans on such an occasion, and her self-reflection of the partisan cultural technique explains her dance performance best:

I became a dancer where nature became my stage. Instead of on a wooden stage, I now dance everywhere. The feeling of balance becomes a “problem” again; the muscles work differently, because a leg may search for support either on stones or on soft ground. This was the first thing I noticed … This immense natural space provides opportunities and calls for the expansion of movement. From restricted motion and gesture in the closed theatre, one can then create a whole march in the open space of a natural stage … In the process of creation, my co-dancer was perhaps left to his own devices more than all other artists, as he had to react to my thoughts without any external help. Alone with his mind and body, this “something” had to be created. Conventional and unpersuasive ballet “grace” would immediately wither away in nature, it would even become comical. In our case … we could speak of dance expression rooted in the liberated ground, with human participation in the historical creation of a nation or a people. It was about the participation in the liberation struggle of people that knew no despair and were aware of their strength and historical mission. Dance calls for a struggle, and in this struggle, it is winning; it unfolds in joy; because of the struggle and constant effort, because of its power and its very historical act … My dancing did not imitate anything that could be associated with formalistic moves. I rejected almost everything that I had learned during all the years of my dance school training. I searched for a dance expression, original and fresh, which emerged from the human need to move. I found it in the game of balance with dynamic, rhythmical, and voluminous dimensions, in the tension and relaxation. Dance expression was a consequence of my internal engagement. That I found this correct language of movement was only possible because of the people and the partisan poetry, which was understood by everyone. (Paulin-Brina 1975: 25–26; my translation and emphasis)

Marta Paulin-Brina – despite being highly skilful in modern dance techniques – had to first “unlearn” these techniques and then relearn them to dance under the new condition, both natural and historical, and in front of a new partisan audience. To dance in a partisan way and in that way, to be a part of a partisan community, and a part of a partisan revolution. The harsh circumstances of war and a long winter march against Nazi forces in Štajerska bore hard consequences for Brina: her toes froze and afterwards she was no longer able to dance. After the war she became a teacher at the Academy and taught a whole new generation of dancers.

Diverse partisan fragments of emancipation and liberation can nowadays be found scattered all across the world, on diverse sites of historical struggles. One of the pivotal contributions of decolonisation advocacy is to uncover such sites, especially in formerly colonised countries in the Global South. Some emancipatory fragments have recently entered national archives and narratives, others were involved in restitution, while a majority of them lay forgotten, demonised, and revised by right-wing recuperations. For me, it is a clear historical task in our counter-archival and re-alphabetisation of the revolutionary past to reconstruct the solidarity of and between the oppressed and make them our contemporaries despite the far temporal and spatial distance. This is not done by decoupling and isolating critical art and culture into new enlightened institutions, but to bring such a call for liberation and emancipation of the oppressed to the fore on the political, and yes, also o the economical stage. The task of a new alphabet today is to defragment such histories of communities-in-resistance and move beyond their sheer nostalgic or spectral imagery since they emphatically call on us to act today for different (lost and to be fought for) futures. There are then many lessons to be learned and also things to unlearn taking in perspective struggles and revolutions of the twentieth century. Their defeat, however, should never be a cement, a blockade, which would force us to accept bitter cynicism that no change is possible globally. In this perspective, development and socialisation of new weapons of mass creation that are subtracted from the neoliberal ongoing creativity seems to become ever more important task.

[1] I took the notion of emancipation from the work of Jacques Rancière. In addition to his more recurring trope on the “intellectual emancipation,” his theory of politics in Disagreement (1999, Minnesota: Minneapolis University Press) makes it clear that thinking collective emancipation cannot be done without rethinking equality. This means that against the dominant order of visibility-sayability-countability, or what he calls “police,” we have politics that demonstrate ruptures and the ways how those that are invisible, uncounted, unsayable not only become visible, but actually shake and disturb the very foundation of how society is structured (1999: 103-104).

[2] For an excellent conceptualisation and journey through the twentieth century see Enzo Traverso’s Left-wing Melancholia: Marxism, History and Memory (CUP, 2017).

[3] I develop this notion as well as redefinition of »weapon« in time of national liberation struggle(s) in my book Partisan Counter-Archive (De Gruyter, 2020). This small contribution relies on theoretical observations and some research findings from the chapter 2 and rereads them through the prism of community-in-resistance.

[4] See Davor onjikušić, Red Glow, De Gruyter: Berlin, 2021.

[5] See Miklavž Komelj, How to think Partisan Art?, Ljubljana (2008: 104-105).

[6] In the sense of Jacques Rancière’s The emancipated spectator (2008).

[7] Miklavž Komelj, How to think partisan art?, založba cf: Ljubljana, 2008.

[8] Deleuze and Guattari, What is Philosophy?, 1994: 176–177.

[9] She attended the school of modern dance in Ljubljana run by Meta Vidmar who got a licence from the internationally renowned school in Dresden (Mary Wigman).