Everyone belongs to the third generation. On trauma as the space of choice.

Speculations

I am a genocide anthropologist and psychotraumatologist. A Polish Jew. A woman who despite political tension (and abuse) has decided to live in Poland, in the land of eternal memory, in “the bloodlands” as Timothy Snyder called it, or “contaminated landscapes” (kontaminierten Landschaften) as Martin Pollack has suggested. I live in Warsaw, in the district of Muranów, built on the ruins of the Jewish ghetto. I deal with war trauma every day. While writing this text, I try to organize my notes from yesterday’s supervision with the participants engaged in a project documenting the liminal experiences of Ukrainian refugees. Sometimes, I think that war constitutes an immanent…

The paragraph breaks off at this point. The words that I am writing set an emotional trap. I launch into an internal, post-traumatic monologue, an inherited statement. A self-fulfilling prophecy, the epigenetics of trauma. The above words about myself are neither untrue nor completely true. Today I am aware that truth begins where fear ends and I am trying to find it in both the present and the potential history (Azoulay 2019).

Ariella Azoulay, an art curator and visual culture theoretician of Israeli descent, understands the notion of potential history in two ways. First of all, it is possible, by looking deeper into hidden archives, to discover the past anew (thanks to still undiscovered and unread sources and new perspectives adopted while reading known documents). Second, it is a synonym for alternative history (including counter-traumatic history), that is, a specific domain of fiction, which takes into consideration alternative and anticipatory versions of the past and based on them, creates space for cognitive and emotional exploration of the present and the future. Of course, one could ask: “Why conduct thought experiments on traumatic historical events if what is done cannot be undone?” But I think it is quite useful. Especially since the phenomenon of trauma itself is usually processual and speculative. Its greatest strength lies in its ability to appear to be “ever-living” and necessary, even if its presence – in one’s post-traumatic life – is unnecessary and painfully inadequate.

***

During my six-year-long field research in Rwanda, I understood how important it was to have a process of reconstructing post-traumatic identities of genocide survivors (both the Tutsi and the moderate Hutu in this case) in order for them to have a sense of dignity and agency. For me, it was also the first moment when I recognized the potential of “potential history.” Offering the possibility for Rwandans to talk about the tragic events, create a conceptual framework and gain consciousness of their current situation, constituted an important element for individual and collective therapeutic work. In this context, artistic activities seem to be just as important. In the capital of Rwanda, Kigali, and other bigger cities, the number of art galleries and ateliers is as high as the number of symbolic commemorations of mass graves. Places of creative work have an egalitarian character and constitute a conscious element of sociotherapeutic action. They gather the accounts of not only the survivors, but also the second and third generations of Rwandans born after the genocide. It should be noted that the birth rate in Central and East African countries is more accelerated than in West African countries, which has a considerable significance in processing the experience of collective trauma.

***

Trauma

In the language of psychology and psychotraumatology, trauma can be defined as a kind of state or condition of a human being. A condition that is the consequence of an event characterized by the presence of a stressor going beyond the range of usual, everyday human experiences. Genocide, of course, shares these characteristics. Among traumatic events, one can also find: wars, torture, natural disasters and traffic accidents. Sigmund Freud developed one of the first conceptions of trauma based on the psychoanalysis of the first big railway disasters. A traumatic event can also be sexual violence (i.e., rape, harassment, etc.), sudden death of a close person, witnessing a murder or accident, or simply experiencing high emotional tension for several days.

Trauma as a response to an injury/stressor can affect all of us. At the level of the body and its physiology, different people may have similar symptoms, primarily resulting from increased production of hormones (such as adrenaline, noradrenaline, endorphins or cortisol), which are activated unconditionally in a life-threatening situation. The overproduction of hormones – understood as a defence mechanism (or dissociation) – is desirable during an injury since it relieves pain and very often saves a life. However, persistent activation of hormones in post-traumatic reality (i.e. in the post-war world in which a human being does not have to function in fight mode) may cause pathological symptoms at the structural level (i.e. insomnia, irritability, tendency to dissociate, neurological symptoms, depression and mania, psychotic disorders, nightmares, strong excitation, apathy, tendency to substance abuse). This state of constant threat, which is experienced at the physiological/internal level but is inadequate for the reality of the outer world, is usually called “trauma.”

This is a freeze-frame from a video interview with Wanda Lurie, a survivor of the Wola massacre. The footage was recorded in 1968 for the Polish Television (Telewizja Polska, TVP), but was never screened. In 1944, the workers’ district of Wola in Warsaw became the site of the tragic pacification of the civilian population. In three days, German SS units exterminated about 25,000 people. Shot more than once, Wanda Lurie witnessed the execution and death of her three children. She survived, left lying unconscious under a heap of dead bodies. During the massacre, Lurie was nine months pregnant. Several days after her own “execution,” she gave birth to a son. She named him Mścisław (an old Slavic-origin name meaning “vengeance” and “fame”). With my students, I often analyze the body language of the survivor in the footage. The way Wanda behaves indicates that she is in a state of complete dissociation. At the bodily level, she is practically absent or, put in the discourse of psychotraumatology, she demonstrates a freeze response. She recounts the history of her survival in a monotonous voice; not a single emotion can be perceived. Her face remains still for 17 minutes of the interview. Being disconnected from feeling can often be the only method of “dealing” with painful memories for a survivor. In the 1960s (and the following years), war trauma was a taboo subject. Moreover, there was no public awareness of, sensitivity to or above all, the possibility of attending individual psychotherapy. It was assumed that “such a person” could be found in every family and thus these were private matters, viewed as something that should stay within the family. In consequence, the mechanism of repression was so strong that its effects are still being experienced in Poland today.

***

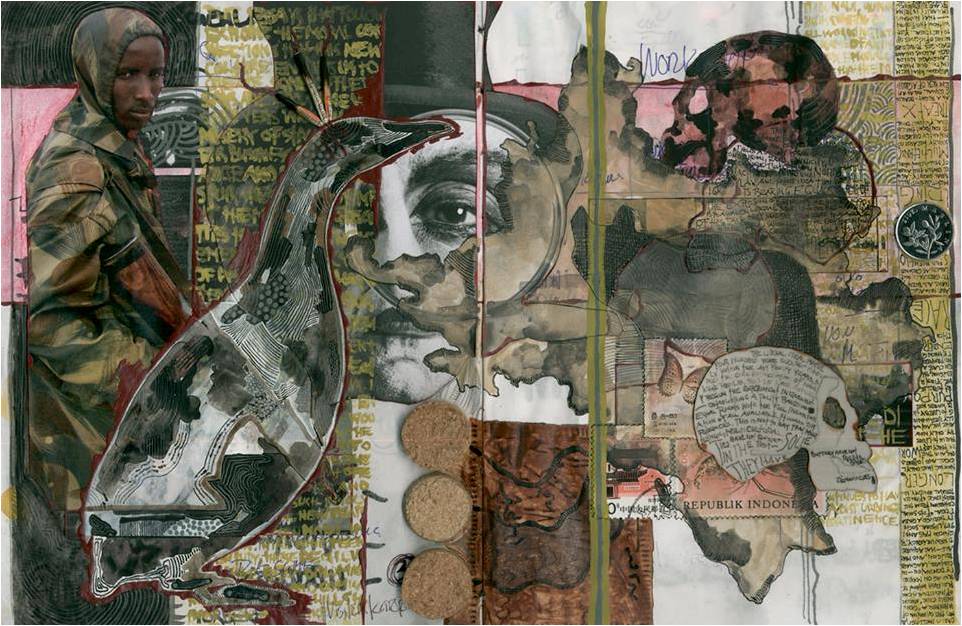

Wolf Böwig is a German war correspondent or rather, former correspondent. Today, his works are displayed in galleries of modern art (https://www.wolfboewig.de/). When we met in 2014, he was preparing himself for a trip to Ukraine to cover fighting in the Donbas region. It was his last trip as a correspondent. Long-term experience of working in the regions of military conflicts left its physical and emotional mark on Wolf. To process difficult memories, he started to create disturbing as well as moving collages that disrupt the dissociative state. The artist combines in his documentary photographs with fragments of maps, field notes and small objects that he collected during his expeditions. Psychotherapy is not the first choice for everyone. Similar to the cases I observed in Rwanda, Wolf has chosen art as a form of therapy. However, as a psychotraumatologist, I would like to emphasize that the way one decides to handle a difficult situation should not increase the sense of loneliness and social isolation. The experience of trauma itself is sufficient to separate one from oneself and the here and now. Therefore, it is better to choose community art houses or art centres than work in solitude.

***

Different cases, in different latitudes, with different symptoms and different intensities in the post-traumatic reality can be recognized as traumatic. However, it should be underlined that although the range of stressors and symptoms is wide, there is a possibility of a similarly individual and (luckily) affirmative way of dealing with difficult experiences. In psychology, the ability of an individual or a group to use inner resources in order to recover, or rather “regain balance,” are called competencies of resilience.

Generations

Understood as a metanarrative, trauma works like a drug. It carries national, ethnic and religious connotations. It evokes a feeling of guilt. Trauma is like a distant cousin, yours or mine, who likes to appear when you least expect it. Trauma likes big events, memorial candles and pebbles on graves. It is not distracted by pathos, quite the opposite. It persuades you to act “in the service” of an important cause. This is the “only” way to real personal dignity. It offers small pleasures, such as reinforcing my identity as a victim…but I refuse. I have been refusing for many years. Its temptations have only one goal: to dissolve me into one body, one being, with no space for alternatives, subjectivity or independence.

There were a few encounters in my past, for which I can thank trauma. Only when I faced trauma (we call it “trauma exposure”) and identified its nature and truly bodily presence, as it also moved my body, I could make a choice that had not been apparent to my grandparents and parents, the representatives of the first and second generations after the Second World War. To choose emancipation.

My ancestors, going back two generations – my grandmother and grandfather who were both Holocaust survivors – had chosen a method of survival based on the freeze response, partial dissociation. The subject of war was almost absent in their post-war life; the narrative they used was a learnt formula: safety as evasive and emotionless. At home, my mother and her sister did not receive affection. Each affective gesture made towards other people ran the risk of moving the quiet heart and the buried memories. I do not blame them. The reality of post-war Poland (and other countries in Central and Eastern Europe) was not a favourable place to create a Jewish narrative nor any free narrative about oneself.

My mother and her sister could not choose. The second generation is often doomed and subjected to “ignorance” and “passivity” inactivity. They do not have the agential access to experiences that could be recognized as the initial source of pain and do not have the factual memory of difficult events. At the same time, they are filled with intuitive, embodied knowledge. For example, children of Holocaust survivors know how to act around a parent so as not to awake the “traumatic I” or move the “wounded heart.” The premonition and feeling of fear are so clear in the second generation that walking on thin ice in everyday family life becomes the rule for social functioning outside the house. Another step, often present in adulthood, is the depressive state. Paradoxically, it can be a turning point since it is a moment when one starts to feel their own (not their parents’) pain. Feeling her frailty, my mother fell in love and started up a family. In other words, she refocused her attention on “more important” matters. However, I know many stories which show other choices than having a family. They are often equally effective in breaking the enchanted cycle of fear.

I belong to the third generation. I chose to try to step outside the comfort zone of post-Holocaust memory and meet with a non-European, Rwandan model of rebuilding the post-genocide identity. Although the Rwandan genocide shares some features with the Holocaust at the level of origins (a similar influence of nationalist ideology on the initiation of dehumanizing processes can be observed), it is an event of a different character. The post-genocidal Rwandan trauma therefore is also different. Gerard Prunier, a historian specializing in African conflicts and affairs, notices that the differences become even more visible when one examines the social and geopolitical contexts of these crimes. He writes: “To understand the complexity of the post-genocide situation in Rwanda, one should imagine a world in which many of the German SS would have had Jewish relatives and in which the post-war State of Israel would have been created in Bavaria instead of the Middle East” (Prunier 2009: 1). The Rwandan trauma breaks Hilberg’s triad of victim, perpetrator and bystander because it is shared by the majority of the society (regardless of ethnic status). Since it occurs at the vernacular level – among neighbors and within families of mixed descent – it becomes, above all else, a deeply personal rather than political challenge. The material (countless mass graves scattered around the urban and rural landscapes) and physical (machete marks left on the bodies of the survivors) dimensions of the Rwandan trauma constitute a trigger which, on one hand, may lead to madness, but on the other hand, may evoke a real need for processing the difficult experience at an intergenerational level. In other words, the Rwandan trauma does not have any chance to remain in the shadow or become taboo. As a consequence, it encourages closeness.

***

The photograph shows one of the places of memory created at the site of execution in Rwanda. Found in mass graves (or in their vicinity), the objects in the photograph are personal belongings of the victims. Many such places of memory are grass-roots initiatives that were not established by any institution. They are not museums but rather “memorial exhibition rooms” which do not comply with the official commemorative model (applied at national and political levels) and therefore, can offer inclusive memory space for both Tutsi and Hutu survivors as well as their children and grandchildren. Places of memory are located near villages and towns and usually constitute not only space for commemoration but also for social activity. In the photograph, one can see an “exhibition” made spontaneously by one of the local conservators a short while before my arrival. The few-months-long stay in Murambi, a grass-roots place of memory, was one of the most valuable ethnographic experiences of my life. Despite being physically close to the representations of death, I had a feeling of belonging to the community of the living.

***

The Rwandan equivalents of the concept of trauma are guhahamura (which means “being paralysed”) and guhahamuka (which means “being overwhelmed with fear”). According to Naasson Munyandamutsa, a Rwandan psychiatrist with whom I had a chance to work with, the etymology of these words is related to the rich oral tradition of Rwandans, especially to love songs (amahamba). Interestingly, the word guhahamura was not initially applied to human beings; it expressed interest in the emotional condition of a calf that was rejected by its mother. In Rwanda, the cow has traditionally been a symbol of royal authority and prosperity and it constitutes a valuable element – in a social and emotional sense – of the cultural landscape. As Munyandamutsa observed: “Not touched by its mother, a calf is lonely, sad and resigned. That is the reason why it needs the special care and support of a human. Different methods of dealing with sad calves are described in special amahamba (love poems) entitled “In praising of cows;” generally, it is all about hugging them.”

I am not against talking about trauma. On the contrary, I believe that “moving” what is frozen (in safe and supportive conditions) may become the first step to processing difficult memories. In my opinion, not everyone has to go to Rwanda (or another place symbolically marked with pain) to break the cycle of their ancestors’ pain. This African country taught me a lesson which I had not learned at home: in every moment of life or generation, you can decide if (and how) you want to communicate the past, the present and the future. The best way is to do it collectively, with your closest ones. And do not to be afraid to show that which changes the rules of play and allows transforming traumatic history into potential history, namely affection. In this context, trauma constitutes not only the space of choice, but also offers a chance for encounter.

***

A tea plantation in south Rwanda, near the Burundi border. It was the first time my mother had left Europe. In celebration of her fiftieth birthday, we spent two months together in the field. My mother worked as a volunteer at a school for blind children in Kibeho. We met every few days. These were joyful meetings.