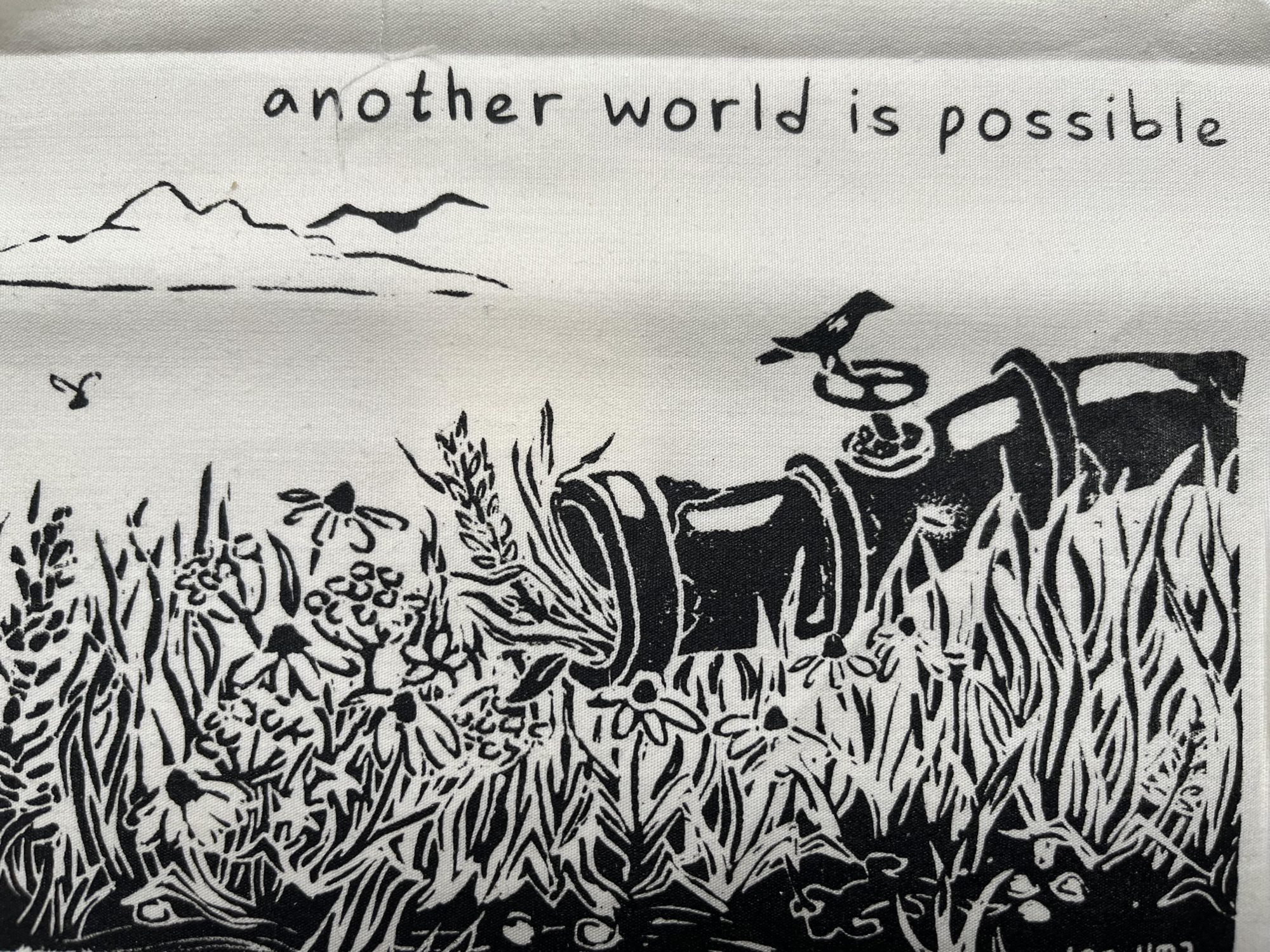

Manoomin Commons*

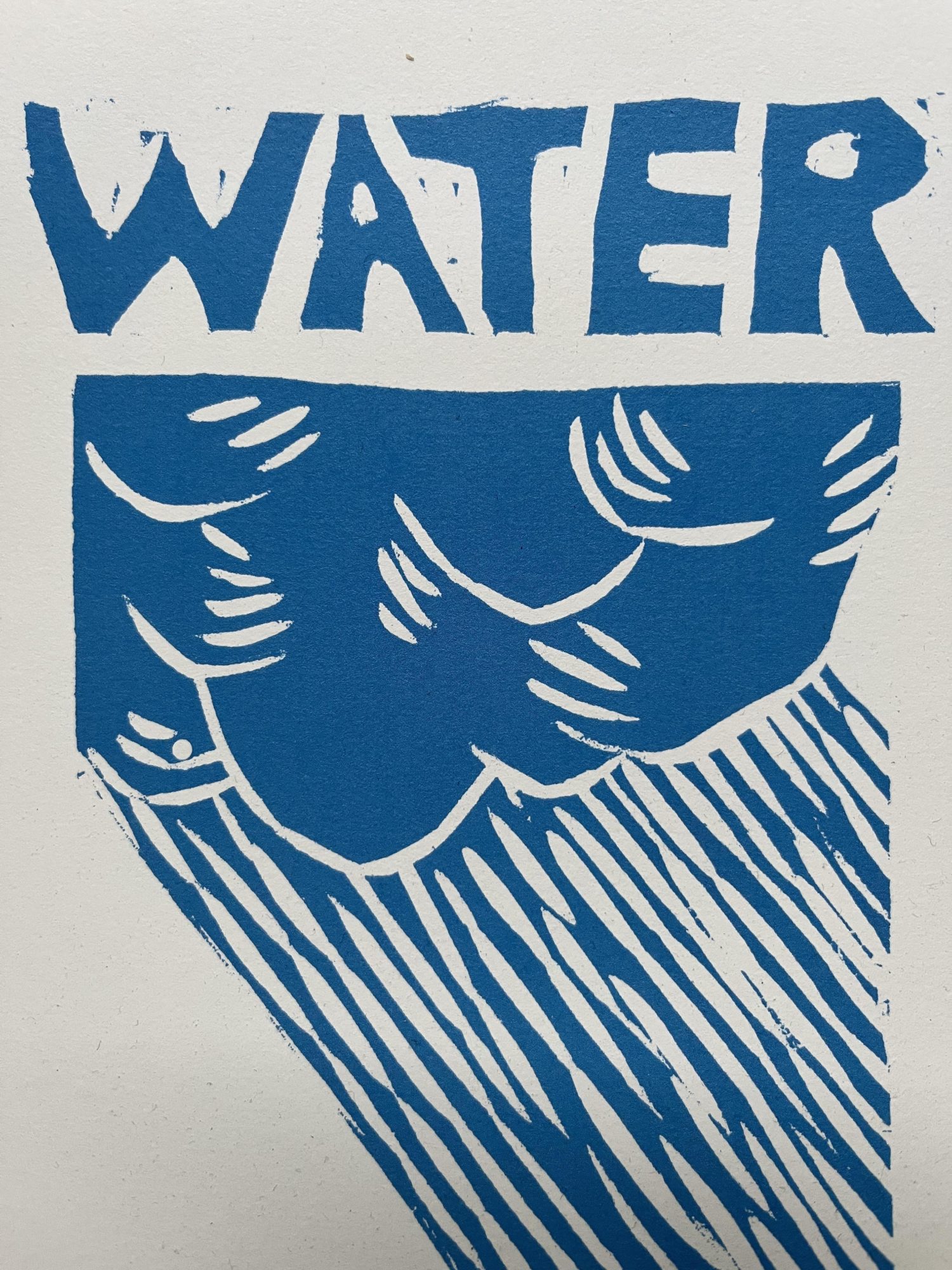

Mother Earth is endangered by “the black snake” as Line 3 of the Alberta tar sands pipeline is aptly called by the water protectors here in the Great Lakes. Line 5, also of the Enbridge Corporation, threatens the waters joining lakes Michigan and Huron. A community subsistence practice of the people of the Great Lakes here on Turtle Island is endangered. The practice is ricing, or harvesting manoomin, or “wild rice.”

The founders of the American Indian Movement or AIM (1968) had fond memories of ricing. Clyde Bellecourt remembers,

“We lived in rice camps as fall came to a close. I looked forward to the rice camps; they would spring up like little villages. People made tar paper shacks maybe a week before they started harvesting the wild rice. Tents, tipis, little cookshacks, and shelters for playing poker – little card rooms – sprung up all over. On the reservation, everyone lived so far apart. Ricing season was a time when I could look forward to seeing all of my friends come together in one place. There would be moccasin games at night, storytelling around the fire, and lots of card games and gambling. The men would gamble bags of wild rice. Winners sometimes went home with a few hundred pounds of rice. Perhaps more than any other time, the rice camps gave us a true understanding of who we were as Ojibwe people. (…) The elders had complete control over all aspects of the wild rice harvest. In the morning they would send somebody onto the water to get some rice grains. If they were still milky the elders would say, ‘Well, you can’t go on this lake today,’ or ‘the sun’s shining on that side of the lake, and the rice is ripe over there, so you can only harvest on that side’.”

Dennis Banks, another founder of AIM, writes, “The men gathered wild rice while the women parched corn and steamed the rice.” He remembered the first time he saw the boats going out for rice. “The rice sticks out of the water, which is about ten feet deep. Stalks of wild rice can be fifteen or even twenty feet tall.” Sharp slivers on the stalks can fly around during the knocking, “so we had to wear bandannas around our faces to protect our eyes.”

And he recalls, “His birth was celebrated by his mother’s friends and relations with a feast of wild rice with deer and moose meat. (…) We lived close to nature, in rhythm with the seasons – fishing, hunting, trapping, ricing, sugaring, berry-picking. (…) The kitchen filled with the scents of these seasons.” He sums up: “The concept of ownership, either of land or of whatever grows or lives upon it, is not part of what Native people believe.”

Banks and Bellecourt made a careful study of William W. Warren’s, History of the Ojibway People, originally written in 1852 (published more than thirty years later) and based upon extensive interviews. He had much to say about manoomin, for example:

In 1761 Mr Alexander Henry, the Englishman, visited Michilimackinac, and met the Ojibway chieftain who addressed him as follows:

“Englishman! Although you have conquered the French you have not yet conquered us! We are not your slaves. These lakes and these woods and mountains were left to us by our ancestors. They are our inheritance, and we will part with them to none. Your nation supposes that we, like the white people, cannot live without bread and pork and beef. But you ought to know that the Great Spirit and master of life has provided food for us in these broad lakes and upon these mountains.”

And he added:

“The hard work [of the women] again commences in the autumn, when the wild rice which abounds in many of the northern inland lakes, becomes ripe and fit to gather. Then for a month or more, they are busy in laying in their winter’s supply.”

Manoomin was the basis of indigenous independence from settler colonialism.

The first Europeans on the Great Lakes didn’t know what to call it. It tasted good, it was filling and nutritious, it stored well. They likened it to oats. By the 1730s a specimen was sent to Linnaeus, the Swedish inventor of binomial classification. Manoomin was Zizania palustria or Zizania aquatic, i.e. of the marshes or the waters. Gilbert White, England’s first ecologist and beloved ornithologist, had a brother, Thomas, who in 1789 quoted Ecclesiastes (11:1) “Cast thy bread upon the waters: for thou shalt find it after many days,” and then reminded his readers in The Gentleman’s Magazine that zizania was the pernicious weed mentioned in Matthew (13:36-43) though it was “of great service to the wild natives.” The parable says that the devil sows zizania which chokes the wheat, the good grain, while farmers slept. The Son of Man sends forth his angels to gather the zizania from the field which shall then be “cast into a furnace of fire: there shall be wailing and gnashing of teeth.” History does not record the Christian who first named manoomin zizania, tying the sacred plant to all that is offensive, iniquitous, and diabolical. A nasty piece of genocidal linguistic sacred text inversion if there ever was one! It is why one must speak of the rights of manoomin.

Manoomin is gathered with canoes. One person standing and polling, and another sitting and knocking. The pole was sixteen feet with a forked foot. A pair of sticks, like a drummer’s, did the knocking, one for gathering a bunch and another for gently knocking the grain into the canoe.

Sioux Shermanremembers, “One early fall day, I went ricing with a friend on a lake so still and quiet that the only sound was that of my rice knockers tapping the seeds that rained into the canoe, of fish jumping, and water lapping. Time stood still. I sensed how this ritual, these earthly rhythms, resounded through generations.”

Richard Horan remembers jigging. “I was a dancing fool! With my big feet stretching out those lovely white moccasins, I twisted and shimmied and swiveled until the balls of my feet were raw and swollen. And it seemed that every time I looked up into the sky, a huge raven was there soaring low over the treetops. There were bald eagles, too, high above the lake, a mile in the air, watching all.”

Tashia Hart bicycled across the Great Lakes gathering stories about manoomin. In the process found solutions to homelessness and its accompanying psychic disturbance. She praises ‘the good berry’ (as manoomin may be translated). She writes, “today our water protectors put their freedom at risk to try to stop the advancement of oil pipelines in watery territories that are the homeland of manoomin. The plants require clean water, just as people do, and a pipeline burst in this delicately balanced ecosystem would wreak havoc for generations to come.”

In fact, the American Indian Movement (1968) started in Stillwater prison. In 1966 Dennis Banks was sentenced to the Stillwater penitentiary for stealing 16 bags of groceries. He suffered nine months in solitary. “I began to read about Indian history and became politicized in the process.” He got out of prison in May 1968. Clyde Bellecourt spoke with intense enthusiasm. “In that moment, AIM was born.” The story was something like this. Clyde Bellecourt was incarcerated at Stillwater and having a bad time of it. Isolated in solitary confinement he fell into existential despair and violent danger. A fellow inmate whistling in the corridor “You Are My Sunshine” caught his attention. That inmate was Edward Benton-Banai who began to teach Bellecourt the history, prophecies, and instructions of his people. Soon they built a drum, then conducted ceremonies, and before long were organizing for liberation, at first in prison, then in the outside, and before long in Indian country, the Red Nation.

The manoomin has been appropriated and the ricers expropriated by gene-splicing, machine-building, gasoline consuming, land-taking, profiteering white guys, who transformed manoomin into a commercial crop and moved it to California, thus forsaking both the people – the Anishinaabe – and the lands at the headwaters of the Mississippi and its lacustrine environs. These are threatened by “accidents” of the petroleum product pumped through pipeline numbers 3 and 5. Pin-hole leaks, weeping seapages, fatigue cracking, or most catastrophic, guillotine ruptures will hurt the lakes, rivers, and estuaries and the creatures therein from ducks to muskrats.

The transference of petroleum entails not only a huge land-grab, but a gigantic transformation of the geology of Turtle Island, as the energy stored by the sun millions of years ago in the form of peat, coal, gas, and oil in order to support a desolated, asphalted landscape relying on the automobile with vast array of supportive administration to maintain the social infrastructure, and whose “side-effects” of methane and CO2 have turned the world upside down by inverting the lithosphere and the stratosphere with dire consequence to the botanical and zoological creations, or Relations as the Anishinaabe might say, in between.

Ervin Oelke has composed a history, Saga of the Grain: A Tribute to Minnesota Cultivated Wild Rice Growers of increased agricultural productivity as a means of economic and social development. This is an aspect of the post-NATO anti-communism following 1949. These are the technicians, the razor scientists, the gene splicers. The white men with baseball caps, steel-rimmed glasses, plain shirts, and polyester pants worn high on the waist. They stand around and consult during a photo op in a grass field or hand out certificates to one another. He did the genetic engineering which was the precursor to the mechanization and removal to northern California of “paddy rice.” This is the old capitalist thing promising one panacea after another – an end to world hunger, a cure of disease – by means of mechanization and production by proletarians.

Airboat, combine, pull-type combine, dragline, harvester, paddy wagon, parcher, picker, rototiller, speedhead, thinner. Wild rice cutter harvester. Floating wild rice thinner. Wind separator. Hullers. Electric pumps to flood paddies. Dams to control depth, dikes. Sportsmen and vacation cabin owners early entrepreneurs. Isolation cages for plant breeding.

The book contains a lavish number of color photographs. I counted 212 people in them. Only fifteen (7%) of them are of native growers. Of the remaining 197 93% are men, and twenty-three are women. Among the native Americans eight are men, seven are women. All fifteen of the native Americans are photographed at work – knocking rice, polling the canoe, parching, jigging and winnowing, while the others, the “pale faces” so to speak, are photographed standing in a field, or next to a big machine, or receiving a certificate, displaying an ad, or glancing at account books. Just posing. It is not difficult to see the difference in the mode and relations of production.

Scott Momaday who so beautifully describes the oscillation between hunting, horticulture, and foraging on the mesa and the twelve hours on the assembly line in the city with cigarettes and black coffee. Of language, he writes, “They have a lot of words, and you know they mean something, but you don’t know what, and your own words are no good because they’re not the same; they’re different, and they’re the only words you’ve got.”

The government regulates. Bureaucracy transforms sound and meaning into ideograms and code. Look at all these unpunctuated abbreviations. The letters no longer stand for sounds or even words. Such kind of coding is widespread in corporations and the Pentagon where it functions as secrecy and exclusion. Obfuscation is the result and occasionally unintended humor.

Consider the PHMSA, Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration of the Department of Transportation, and its OPS, Office of Pipeline Safety. Or, consider the PIPES, Protecting our Infrastructure of Pipelines and Enhancing Safety act of 2020, which mandated that PHMSA update the regulatory definition of the USA “Unusually Sensitive Areas,” which are a subset of HCAs, High Consequence Area, to include the Great Lakes, coastal beaches, and coastal waters. Here the IM of the HL (the integrity management of the hazardous liquid) and the IM of the GT (the integrity management of gas transmission) combine to form the HLIM and the GTIM with ILI (in-line inspection), sometimes under an IFR (interim final rule) by a POQ, pipeline operator qualification. As the face of the settler-colonial breaks into a shit-eating grin, in this stupid kind of codification the USA becomes an “unusually sensitive area.”

“Cultivated wild rice” is an oxymoron written with a straight face. But what is the meaning of “wild”? “In wildness is the preservation of the world,” wrote Henry David Thoreau. The world, indeed, is at stake.

The rice grows on the water. However, Water Protectors have emerged, and they can give us hope as world energy and food systems are damaged by war. The hope derives from experiences of mutuality. It derives from many generations of survivance by First Nations and Indigenous folks transmitted by grandmothers over kitchen fires through story and even prophecy. Now the story is preserved by native food sovereignty, restaurants, books, videos, and prophetic ways of remembrancing.

The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway is a book designed for generations hence. “Mishomis” means “grandfather” in the Ojibway language. It tells the Ojibway creation story, how original man walked the earth with his grandmother, the earth’s first people, the flood, Waynaboozhoo (the name of original man), the seven grandfathers, the Medewiwin ceremony, the clan system, the pipe, the eagle, the sweat lodge, then of special interest, the seven fires and seven prophecies, containing the migration of the Anishinaabe, and stepping into modern history.

Seven prophets left the people with seven prophecies. “Each of these prophecies was called a Fire and each Fire referred to a particular era of time…” and a particular place. They lived peacefully in the east by the salt waters of the Atlantic. The first prophet told the people to follow the sacred shell to the Midewiwin Lodge, that is, to travel west and not to stop until they come to a land where the food grows on the water. This is the ur concept of the people, the Anishinaabe people (Ojibway, Ottawa, and Pottawatomie).

The second prophet says the Anishinaabe people will weaken, lose the sacred shell, but will find stepping stones pointed out to them by a child.

The third prophet says the Anishinaabe will find the path to the chosen ground, a land in the West to which they must move their families. This will be the land where food grows on water. This will be the big lakes, Superior, Huron, and Michigan.

The fourth fire was given by two prophets telling of the coming of the light skinned race. One prophet says they will bring new knowledge and brotherhood. The other says they will bring death and destruction. “if the rivers run with poison and fish become unfit to eat” you will know which is which.

The fifth prophet spoke of struggle and false promise. Light-skinned people make war and take the land. The Ojibway called them the Long Knives. The sixth Fire says that the children will cease to listen to elders, the ceremonies will die out, sickness will prevail, and “the cup of life will almost become the cup of grief.” This was the time of the Indian schools. The teachings are forgotten.

The seventh prophet was young and had a strange light in his eyes.A new people will emerge, and they will retrace their steps to find what was left by the trail. Two roads are available, technology or spiritualism. Which of these two clashing world-views will win? It might be possible to return to the first prophet at the time of the Fourth Fire, the path of peace and harmony. Edward Benet-Banai concludes, “Are we the New People of the Seventh Fire?

Let us take this advice from the Seventh Fire to go back and retrace our steps. Kondiaronk, the Huron leader and eloquent indigenous critic of European “civilization,” was born in 1649. In Europe that was the year that King Charles I head was chopped off by Oliver Cromwell, the aggressive privatizer and champion of enclosure. With gunpowder and cavalry Cromwell also put an end to the Levellers (the folks who gave us the phrase “We the People”) as well as the Diggers (“the earth is a common treasury for all mankind without respect for persons”), thereby draining the meaning out of the word “common wealth.”

David Graeber and David Wengrow, esteemed anthropologist and archaeologist respectively, begin their work The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by quoting Kondiaronk. They mistakenly call him “the Rat” when they mean “Muskrat,” a different creature entirely, akin to the beaver not the rat. Here let’s remember how Turtle Island got its name, that is, the origin of the Earth. Before it existed there were the primordial waters. Sky woman sent one animal after another to dive deep to fetch some dirt from the bottom of the oceans, but none could do it until Muskrat tried and succeeded in bringing up some dirt that he placed on Turtle’s back. Turtle had kindly offered it for this purpose and from there Earth grew to its present condition. It is a tale of dependence on fellow creatures, Turtle’s generosity and Muskrat’s bravery.

Kondiaronk carried the name of the creature who helped originate the world. He spoke in Michilimackinac. He opposed European selfishness, blind submission to authority, law based on punitive principles of torture and differentials between rich and poor.

“I still can’t think of a single way they act that’s not inhuman, and I genuinely think this can only be the case, as long as you stick to your distinctions of ‘mine’ and ‘thine.’”

“You honestly think you’re going to sway me by appealing to the needs of nobles, merchants, and priests? If you abandoned conceptions of mine and thine, yes, such distinctions between men would dissolve; a leveling equality would then take its place among you as it does now among the [Huron].”

In 1887, a year after Haymarket when a mood of repression still prevailed, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs J.D. Atkins, former slave owner (1825-1908), wrote “The Indians must be taken out of the reservation through the door of the General Allotment Act, and he must be imbued with the exalted egotism of American civilization so that he will say ‘I’ instead of ‘we,’ and ‘this is mine’ instead of ‘this is ours.’” The Dawes Act of the same year destroyed indigenous common lands. Atkins supervised the notorious hair-cutting, language forbidding, brutalizing culture destroying Indian schools beginning at Carlisle. “Education for extinction” sums up the policy.

The old Haymarket slogan – Eight Hours of Work, Eight Hours of Rest, and Eight Hours for What You Will – no longer gets to the nub of the matter because it does not concern social reproduction. Work, rest, and play, as such, do not inherently entail ecological safety. How will work, rest, and play protect the water? How will work, rest, and play nurture the ground? How will work, rest, and play clean the air? How will work, rest, and play control the fossil fuels?

We must resolve these questions. The worker must become a protector. The worker takes control of production and its speed, its organization, its tools, its product, and above all its purpose. It must subordinate quantitative abstract value to its qualitative, concrete effects on water, earth, air, and fire. And if it does not know how to do this, it must learn from those who do. Those who do are the wageless, the mothers and housewives, the indigenous and colonized, the slaves, the hewers of wood and drawers of water, even the children – especially the children. For them subsistence is not, by definition, a quantitative issue. It is always an issue of uses. Survival or survivance.

At each step, therefore, in the history of the working-class we must closely examine the relationships to those who are unwaged, those who do not live by money, because in our current epoch money answers nothing! It did in the past but at the expense of huge divisions, terrible splits, and separations that felt eternal.

The iron workers led the eight hour movement. The combine machine combined harvesting and threshing work that had formerly been done by hand with sickle, scythe, and flail (though with each tool more than hand was at play). This machine will shave the grain of the prairie like a razor. In Chicago they built combines for McCormick who cut their wages by 15% then installed pneumatic molding machines to eliminate the need for their skills. They struck on May 1, 1886. The police shot some. Outrage swept through Chicago’s workers. A meeting was called at the Haymarket where, as the sun set, a bomb was thrown and seven policemen and four workers were killed.

No one asked the iron molders or the metal craftsmen at the combine works of McCormick whether they were proud to be producing the machines which would clip the prairie grains far quicker and closer to the ground than the hand-held sickle or the swaying scythe. He did not know that the resulting monoculture, though seeming to feed the world, created the dust bowl. Indeed since the end of the Civil War the iron workers led the struggle for the eight hour day. When he was shot down by police for this, he aroused the collective ire of fellow-workers of Chicago to assemble. The rulers of this Gilded Age closed ranks and howled against Apaches and anarchist alike as “terrorists.” Geronimo surrendered in 1886. Wounded Knee massacre occured in 1890.

Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, George Engel, Louis Lingg, Samuel Fielden, Oscar Neebe, and Michael Schwab were convicted of conspiracy to commit murder and sentenced to hang. These are the Haymarket martyrs, and four of them were hanged on 11 November 1887. This was a crucial year in the history of mine and thine. The buffalo had been exterminated, the Lakota starved. Sitting Bull was gone, Geronimo too. Tolstoy published his wonderful parable against the property statute. The commons was being taken away world-wide. August Spies famously predicting, “There will come a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today.” The power of that silence is still ringing.

Albert Parsons whose partner, Lucy, was descended from native Americans, spoke. August Spies had lived several months with Anishinaabe people in Canada. Spies had lectured on socialism when “the necessity of common ownership in the means of toil will be realized, and the era of socialism, of universal cooperation begins.” Albert Parsons had written two years earlier:

“The Indian has been ‘civilized’ out of existence and exterminated from the continent by the demon of ‘personal property. Their lands appropriated by ‘law,’ the surveyor’s chain reaching from ocean to ocean, driven from the soil, disinherited, robbed and murdered by the piracy of capitalism, this once noble but now degraded, debauched, and almost extinct race have become the ‘national wards’ of their profit-mongering civilizers. Under the aegis of ‘mine and thine,’ barbarism became so cruelly refined that man prospers best and only when he exterminates his fellow man.”

According to Greek mythology “aegis” was the shield of Zeus, the god of gods. It also meant a violent thunderstorm striking fear everywhere. Land, machine, and work fell under this aegis. Mechanization of agriculture relied on iron, the iron came from Mesabi range in Minnesota, the iron mine workers were Slovaks, Finns, and native people (Ojibway). Metal workers made and invented machines to remove manoomin from Ojibway control after 1949 when Truman announced NATO and world-wide agricultural development (the “green revolution”) in the same speech. In the 1960s significant leaders of the American Indian movement were iron workers, especially the prophet, Eddie Benton-Benai, also Bellecourt and Banks. The story of Indians in the working-class movement or the labor movement has not been well-told. Frank Little of the IWW was lynched in 1917. There’s the Anishinaabe man, “Hap” Holstein who was active in the Minneapolis teamsters strike of 1934 which, together with strikes in Toledo and San Francisco, pushed for a New Deal of relief, welfare, and security. The most famous iron workers perhaps were the Mohawk sky-scraper builders who set and joined with hot rivets the beams and struts up there with the clouds in the sky – the Golden Gate Bridge, the Empire State Building, the Twin Towers, etc.! They belonged to the League of the Haudenosaunee.

Honoré Jaxon, the “prairie visionary,” was connected with the leadership of the Ojibway people and their relations in the struggle that led to the political formation of the province of Manitoba. Louis Riel, a métis or what the Canadians call mixed Anglo and Indian, led the Red River resistance of 1870 following the first appearances of land surveyors, and then led the Rebellion of 1885. He was hanged by the Anglo Canadian government in November 1885. Jaxon, his secretary, fled to the USA, assumed Anishinaabe identity, followed the commons principles of Henry George, arranged for the publication of the last words of the Haymarket martyrs, became an active ally of Lucy Parsons, the anarchist Voltarine de Cleyre, and Mary Elizabeth Lease of Kansas (“raise less corn and more hell”). He advocated “the Indian’s view upon the land question.” A couple years after Wounded Knee massacre he joined Coxey’s army of the unemployed marching behind Jasper Johnson, the Afro-American standard bearer, on their way across the mid-west to Washington D.C. For a living he built side-walks with his own hands.

In Minnesota the Stillwater prison received its first inmates in 1853. Prisoners made agricultural equipment. More than a thousand prisoners made engines and threshing machines until the Minnesota Threshing Company failed in 1894. This same prison also produces the oldest continuous prisoner operated newspaper, The Prisoner Mirror, partly financed by the Younger brothers, the famous 19th century bank robbers. So many Ojibway and Dakota people passed through the prison that it might seem nothing more than an extension of the rez.

The Lakota man, Henry Standing Bear, was his friend. Jaxon said, “Study the Indian and his ways,” he said, “if you would find the light which alone can save the white man’s civilization.” His mother and brother lived on the rez in Saskatchewan. Later he allied with a son of the Zapotec, Ricardo Magón. He fled across the border and soon changed his name to Honoré Jaxon, and allied with the Haymarket martyrs. He visited them in jail, he saw that their speeches were published. He began to collect and to preserve the oral records of the struggles on that part of Turtle Island. Time went by. His collection grew and grew until it came to be measured in tons.

The settler, white, war-making, patriarchal ruling class is not content to take the land, extirpate the culture, exterminate the people, and in so doing create propertyless, homeless, expendable proletarians. If the division between the water protectors and the workers, between white skins and those whose skin is the color of the earth, is to be preserved as a means of capitalist governance, it must erase the memory too of our struggles.

Jaxon was evicted from his basement apartment on West 34th St., N.Y., in 1951, and all his archives which certainly would have helped us tie the common themes of life and spirit of the indigenous people to the movement of the poor laboring proletarians of the capitalist city, were thrown in a pile on the street where they were sold off as “waste paper.” Many thousands were thrown off the rez or ceded land to make a “living” as proletarians.

There is one other theme, if you will bear with me. I mean law and the people whose backs are against the wall. The anarchist tries to think free of law. To the poor, law often means little more than a knee on the neck, or the clanging prison gate. The romantic will sing the praises of the outlaw. The theologically inclined will adhere to grace not law, and be an antinomian. At the moment one of these is the legal innovation called “the rights of nature.” A brief on behalf of the rights of manoomin was submitted last year. It goes back to the U.S. Constitution. Evelyn Bellanger of the White Earth Reservation helped establish Rights of Manoomin, “a gift from the Creator or Great Spirit and … possesses inherent rights to exist, flourish, regenerate and evolve, as well as inherent rights to restoration, recovery, and preservation.” Why does not the bill of rights include the rights of manoomin when little was more significant to life than it and its waters?

In 1796, a novel much praised by Mary Wollstonecraft, called Hermspring; Or, Man As He Is Not, was set partly in Michilmackinac. Its protagonist opposed the ethos of mine and thine. Turtle Island needs to constitute commons all over because the present constitution at its origin was a deliberate application of law to smother the commons which was sold away in uniform, little squares of mine and thine as the surveys of US imperialism. If you doubt this the evidence will be found in the first lectures given at the University of Pennsylvania law school by James Wilson. He was one of George Washington’s Supreme Court justices. He devised the notorious three-fifths clause of the USA Constitution. He “owned” as private property vast areas. He explained in his lecture how that Constitution was against the principles of the commons.

To conclude: the working-class, the co-creators, must become protectors of water, air, and earth at all costs by every means possible, as we gracefully install by our acts of commoning the sublime transition to the epoch of rest, peaceably if we may and forcibly if we must.

References and Suggestions for Reading

Dennis Banks with Richard Erdoes, Ojibwa Warrior: Dennis Banks and the Rise of the American Indian Movement (Norman, Oklahoma: U.O.P., 2004)

Barbara J. Barton, Manoomin: The Story of Wild Rice in Michigan (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2018)

Clyde Bellecourt, The Thunder before the Storm (St. Paul, Minnesota: MinnesotaMinneapois Historical Society Press:, 2016)

Edward Benton-Banai, The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway (St. Paul, Minnesota: Red School House, 1988)

Jonathan Carver, Travels through America in the Years 1766, 1767, and 1768 (1778)

Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States (Boston: Beacon Press, 2014)

James Taylor Dunn, “The Minnesota State Prison during the Stillwater Era, 1853-1914,” Minnesota History (December 1960)

Nick Estes et al, Red Nation Rising: From Bordertown Violence to Native Liberation (Oakland, California: PM Press, 2021)

David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (New York: Macmillan, 2021)

Tashia Hart, The Good Berry Cookbook: Harvesting, and Cooking Wild Rice and other Wild Foods (St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society 2021)

Richard Horan, Harvest: An Adventure into the Heart of America’s Family Farms New York: HarperCollins, 2011)

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013)

Johann Kohl, Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings Around Lake Superior (1860)

Winona LaDuke and Brian Carlson, Our Manoomin, Our Life: The Anishinaabeg Struggle to Protect Wild Rice (Minnesota: White Earth Land Recovery Project, 2003)

Baron de Lahontan, New Voyages to North America, English translation (1703), reprint Chicago 1905, edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites.

Aylmer Bourke Lambert, “Observations on the Zizania aquatica,” Transactions of the Linnean Society, volume 7 (1804)

Peter Linebaugh, The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day (Oakland: PM Press, 20)

Andro Linklater, Owning the Earth (Bloomsbury, 2013)

N. Scott Momaday, House Made of Dawn (1968)

J. Raleigh Nelson, Lady Unafraid (Idaho: Caxton, 1951)

Ervin Oelke, Saga of the Grain: A Tribute to Minnesota Cultivated Wild Rice Growers (Hobar Publications: Lakeville, Minnesota, 2007)

Dave Roediger & Franklin Rosemont, Haymarket Scrapbook (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr, 1986)

Thomas Paine, The Rights of Man, part one (London, 1791)

Sioux Sherman with Beth Dooley, The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen (University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 2017)

John Thelwall, The Rights of Nature: Against the Usurpation of Establishments (London 1796)

Leo Tolstoy, How Much Land Does a Man Need? (1886)

David Treuer, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present (New York: Riverhead Books, 2019)

Thomas Vennum, Jr., Wild Rice and the Ojibway People (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988)

William W. Warren, History of the Ojibway People, second edition, edited by Theresa Schenck (St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2009)

Thomas Holt White, “Natural History of the Wild Rice,” The Gentleman’s Magazine (1789)

Anya

Zilberstein, “Inured to Empire: Wild Rice and Climate Change,” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 72,

no. 1 (January 2015)

* This is an edited and shortened version of an essay first published in Counterpunch. I thank Michaela Brennan for near daily messages concerning Line 3 and the Giniw Collective; I thank Peter Rachleff of the Minneapolis St. Paul East Side Freedom Library; I thank Silvia Federici and the students of her Binghamton commons seminar; and I thank Julie Herrada of the Labadie Archive of Michigan.