Petrichor and the Planetary Sublime

Have you ever looked up in a rain shower after a long hot summer to watch the drops of water? As if in slow motion, you might see your reflection, the sky above, or the canopy of trees. Now watch the raindrops fall to the ground—bits of sky meeting the earth. You have just witnessed the dispersal of petrichor—made from contact between atmosphere and soil.

The science of rain

Petrichor is the scent of wet earth when it rains. We often think of it as pleasant and refreshing, strongest when it rains after a dry spell. There are several components that contribute to the scent of petrichor: aerosols that adsorbed into dry clay and silicate material in soil, a molecule called geosmin secreted by bacteria, and rain that disperses the scent. There is often a comparison between scent and sound, and so these individual components form a symphony of what we come to know as petrichor.

It is interesting to think about petrichor as a planetary scent that can promote healing and unity in a fragmented society. But first, let us discuss its individual fragments. Petrichor is a collection of molecules and is a meeting of the earth and atmosphere. Mineralogists concluded that it came from the remains of dead plants and used to call it “argillaceous odour”. But it was only in 1964 that Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) mineralogists Isabel Joy Bear and Richard Grenfell Thomas chemically described this scent in Australia. They noted that this odour is strongest in arid regions with little organic, and that the scent was not limited to clay, but also to the majority of silicate materials and rocks as well as materials rich in iron oxide. Organic material was not necessary as igniting these materials to kill any microbes still resulted in the scent1; the bacterial geosmin in the soil contributes to the earthiness of petrichor and in a way serves as its terroir. Bear and Thomas named this scent, “petrichor”, from the Greek “petra” or “stone” and “ichor” or the “fluid that flows in the veins of the gods.”

It was this scent with its Australian nomenclature that brought me to do a PhD in Sydney. In the years prior, my background in molecular biology, fine art, and interaction design had led me to do interdisciplinary work about the environment in more than ten countries. A significant part of my art practice elaborates on our relationship with nature through sensory projects, such as my olfactory piece, The Ephemeral Marvels Perfume Store, a perfume line of things we could lose in the natural world because of climate change.2 Scent is a fascinating starting point because of its invisibility and intimacy, its visceral effects on retrieving memories at odds with our abstract notions of olfaction. While we have various ways and media with which to engage with senses such as vision and hearing, smell is still usually relegated to the commercial world of perfumery that advertises ideas of persuasion and consumption. Or on the other side of the spectrum, there are works in literature and film that examine scent through more extreme ways, such as the murderous villain Grenouille in Perfume: A Story of a Murderer or the more modern German TV crime series based on the book. As well, each city and ecosystem I have done work in has given me many episodes of rainfall, each petrichoric breath reminding me of memories of an Amazonian downpour, a Manila monsoon, or a New York thunderstorm.

Cultures of rain

There are many names for petrichor in different languages. In India, petrichor is distilled into perfume known locally as mitti attar. In Filipino, petrichor is called alimuom. In Korean, 흙냄새 (heulgnaemsae; “earthy odour”). In Chinese, 潮土 油 (Cháo tǔ yóu’; “fluvo aquic oil”). In Finnish: sateen tuoksu. While petrichor seems like a modern discovery, it has long figured in many cultures, concretizing the existence of an ephemeral scent and with it, our memories with rain.

In addition, petrichor impacts behaviour in both non-human and human species alike. In their initial petrichor research, Bear and Thomas noted that drought-stricken cattle seemed restless when this scent dispersed with the wind.3

Petrichor and Indigenous knowledge

Petrichor contributes to the formation of Indigenous knowledge, as I continue to discover here in my new base in Sydney. For example, Anthropologist Diana Young studies the traditions of Aboriginal people in the Western Desert in Australia, and discovered that they link the smell of rain to the colour green in what she describes as “cultural synesthesia”.4 The Anangu, Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara Aboriginal people living in the Western Desert of Australia connect the smell of petrichor with the colour green. The smell of petrichor, most potent after a long dry spell, signals the new growth that is to come on the surface of the land. While the connection of two senses is known in western science as synaesthesia and relegated to the brain, for the Anangu it effects a transformation of the whole body. Young further elaborates that in the dry Western Desert, having a reliable water source is especially important to the Anangu people, who view the land as itself an animated body.4 The vitality of petrichor that is dispersed with rain thus becomes transformative to human and non-human bodies alike. Overall, petrichor is connected to the Ancestral potency of the land. It becomes the olfactory indicator of all that new rains and their related cycles of growth and rebirth promise to the land as well as the mediator between the land and the body.

The combustion of petrichor

But this connection between land and body is threatened by environmental impacts. Petrichor as a scent that incorporates various molecules entangles with many things, but here I focus on fire. The latter is a consumer, an eater of worlds. It needs three things to exist, which are commonly diagrammed in the “fire triangle”: fuel, heat, and oxygen.5 A eucalyptus tree in the Blue Mountains that has been voided of all moisture in a hot dry summer can encounter a spark blown by the wind and ignite, first burning the leaves as they are quicker to digest while the bark which contains the more flammable oil will be ablaze with greater intensity. Fire can spread and set alight an entire forest as long as fuel, heat, and oxygen are all available. A hazard to both infrastructure and human health, fire can spread to communities, with the flames damaging buildings and the particulates choking living beings. Fire has multiple names in different languages, and in English we generally use “bushfire” when referring to fire in the Australian bush, and “wildfire” in other countries.

Fire is an important part of the natural cycle that supports ecosystems. It can create space for new flora to grow and for more sunlight to reach the ground, giving animals a new food source and habitat. Fire can also kill pests and diseases that harm plants and trees. Many botanical species have adapted to use fire, which allows some plants to release seeds. Some plants even require intermittent burning to complete their life cycle. Finally, fire can burn decaying organic matter and return them—and nutrients—back to the soil.6 Culturally in Australia, Indigenous fire management has been used for centuries to take care of the land.7 In a way, petrichor and fire can work to signal various seasons, managing the vitality of the land as we have seen in the Indigenous perspective. But while rain and fire naturally occur in cycles, anthropogenic climate change is upending this balance, threatening the scent of petrichor itself. Bushfire seasons become longer or more intense and our encounters with petrichor may become rarer. As well, rain on a landscape ravaged by bushfire does not smell the same. The fresh earthy scent of petrichor is marred by the sharp bitter odour of burning organic matter, eventually petering into the rotting wet smell left by extinguished flames on devastated landscape. The chemical bonds that hold the molecules of petrichor together are broken, and petrichor together with all organic matter burns to form ash and other remains. Similar to the breaking of petrichor molecules, so too do we break our bonds with the planet as we continue with our relationship with fossil fuels and capitalism.

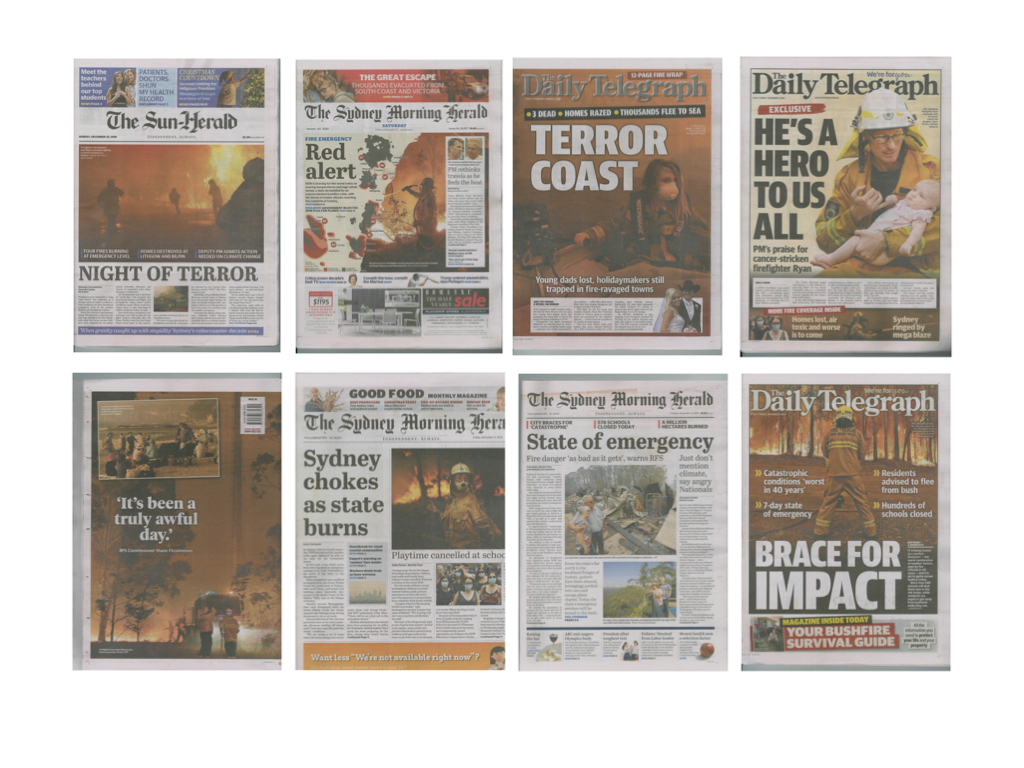

What happens when petrichor combusts? The bushfire season from 2019-2020 (nicknamed the Black Summer) was the worst in recorded history, with 10.7 million hectares burned, in particular destroying the south coast of New South Wales, the Blue Mountains, East Giuppsland in Victoria, and Kangaroo Island off the South Australian coast.8 The scorched earth together with the ongoing drought implies that normal petrichor genesis is impossible until the soil is allowed to regenerate to give time for the plant oils to accumulate and for bacteria to grow and secrete geosmin.

In my sculpture series, The Weighing of the Heart, I cast bushfire ash remains into human heart sculptures to reflect on how bushfires impact our memories of the environment and specifically, petrichor. The title references the scene of the “Weighing of the Heart”, a spell in the Egyptian Book of the Dead in which the heart of Imhotep is weighed against a feather. If the heart fails to balance it will be eaten by the beast, Ammut, and Imhotep will be condemned. If the scales remain balanced, Imhotep enters the afterlife with the other blessed dead. To the ancient Egyptians, it was the heart instead of the brain that is the seat of emotion and memory. The heart was the most important organ of the body and what remains after death—and therefore the key to the afterlife.9 In casting the ashes with resin, I arrest metabolism of the remains back into the soil, creating artistic objects whose solidity is in contrast to the ephemeral nature of both petrichor and human memory.

A planetary scent for healing

The ephemeral nature of petrichor echoes the vanishing of our ecosystems; a heightened awareness of this precious set of molecules may be a way to heal as we continue to navigate our post-colonial world. The near-universal scent of petrichor—integrated in some Aboriginal cultures but vastly separate from the daily lives of the Western world—may allow for a cognitive shift in awareness in a way that makes us feel like active participants that are transforming and are being transformed by this scent where we have the agency to remediate and propose a different way of living on our planet. Perhaps petrichor can be one of those invisible yet potent forces that may promote healing in our broken world. An important step, therefore, is for us to re-examine its importance in our lives. So the next time it rains, step outside and make sure to take a whiff.

References

Bear, I. J. “Genesis of Petrichor,” Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 30, no. 9 (1966): 869–79. Accessed doi:info:doi/.

Young, Catherine Sarah. “Subversive Art: Communicating the Climate Crisis on a Planetary Scale.” In Communicating in the Anthropocene: Intimate Relations, edited by Alexa M. Dare and C. Vail Fletcher, 393-396. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2021.

Bear I. J. and R. G. Thomas. “Nature of Argillaceous Odour,” Nature 201, no. 4923 (1964): 993–95. Accessed doi:10.1038/201993a0

Young, Diana. “The Smell of Greenness: Cultural Synaesthesia in the Western Desert,” Etnofoor 18, no. 1 (2005): 61–77.

National Fire Protection Association accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.nfpa.org/News-and-Research/Publications-and-media/Press-Room/Reporters-Guide-to-Fire-and-NFPA/All-about-fire

Bond, William J., and B. W. Van Wilgen. Fire and Plants. London: Chapman & Hall, 1996.

Lindenmayer, David., Stephen. Dovers, and Geoffrey John. Cary. Australia Burning : Fire Ecology, Policy and Management Issues. Collingwood, Vic.: CSIRO Publishing, 2003.

McDougall, Derek. “Australia’s Bushfire Crisis,” Round Table 109, no. 1 (2020): 94–95. Accessed doi:10.1080/00358533.2020.1721757.

Carelli, Francesco. “The Book of Death: Weighing Your Heart,” London Journal of Primary Care 4, no. 1 (2011): 86–87.