The Impossibility of Community Building in Cuba

Trying to build a community in a totally state-controlled society is impossible. I have seen the people of my generation[1] – including myself – who had to leave Cuba, a totalitarian and leftist country, or lost the opportunity to occupy, speak out and be heard. The demand for freedom of expression as a civil right which includes the legalization of public demonstration and decriminalization of political opposition – a demand led by artists since the 2020 protests – is intolerable to the Cuban State. As a result, they expulsed those in opposition from the country and threatened and/or imprisoned artists, journalists, and activists.[2] Although this repressive response has recently increased, it has been active for the last 60 years after the revolution.

I have come to realize, in this context, that it’s prohibited to build a community in the sense of organizing politically. The only community we have is that of communally failing at organizing protest or a critical discourse. The Cuban Communist Party, both a state and a Party, wants nothing outside of the state to exist: no kind of social relation, no kind of intellectual or affective connection. That is the ideal totalitarian system (Todorov, 2002).

Nevertheless, the Cuban State holds its political legitimacy through a leftist rhetoric, acting as an anti-hegemonic, anti-imperialist and anti-capitalistic system. It has been the excessive demand for participation by the state[3], the repression and the censorship of any kind of community building possibilities that has mobilized Cuban artists at different times during the last decades. Cuban artists have been dealing with a highly ideological spectatorship that promotes participation more than anti-capitalism. Some art critics and anthropologists interested in participation defend this position as a way to restore social relations in the face of neoliberal individualization promoted by capitalism. Through art and fieldwork, they argue that the spectator’s emancipation will occur through participation.[4]

I argue that the work of Cuban artists responds to the fact that the possibility of building a community is negated by the total control of the state that has also affected various relations among citizens: social, political, or affective. Hence Cuban contemporary artworks confront capitalism and the actions inside a totalitarian system with their protests, actions and interventions into the public sphere which in turn creates a community in spirit where real mobilization and communality has been made impossible.

In this article, I argue that there are hidden ways to participate in the Cuban art scene within a state controlled society: Artists who emancipate the spectator through action in public spaces, those who look for non-official narratives, artists that have a cynical response to the excessive demand of participation of the state and its moral statement, and last but not least, artists who produce more than a symbolic action, but rather a civic one aided by legal resources to demand a constitutional change. In this latter case, the artists occupy the public space in collaboration with the citizens of Cuba are regarded as emancipated spectators.

I am the author of one of the artworks I analyze here, I am friends with most of the artists I mention, and I also saw most of the artworks I describe in this essay. In the last five years, many of the artists that have left the country ten or even thirty years ago came back to visit the island.[5] Encounters with them were an opportunity for me to rethink Cuban art history based on their work and their reasons to emigrate. I am writing as an anthropologist looking for theoretical arguments, but also as someone who is part of the Cuban art scene.

The need for emancipation.

In 1984, the artists Juan-Sí González and Jorge Crespo, who is also a lawyer, created the group Art-De (Arte y Derecho / Art and Right). They were both concerned about human rights in the context of Cuba. Crespo was the son of a political prisoner and because of this, it was difficult for him to find a job. González on the other hand was fired from his job because he refused to be part of a repudiation act. Thereby, both of them suffered the consequences of responding to the state by producing artistic actions that allowed for the discussion of freedom of expression in public spaces.

The group Art-De performed several actions between 1984 and 1991. All of them took place in public spaces. They started their actions in a central bus stop in Havana City: the two young artists carried politically charged and often sexually explicit paintings with them while they were waiting for the bus. This led to people asking them about the images and after a while the political police detained and interrogated them both.

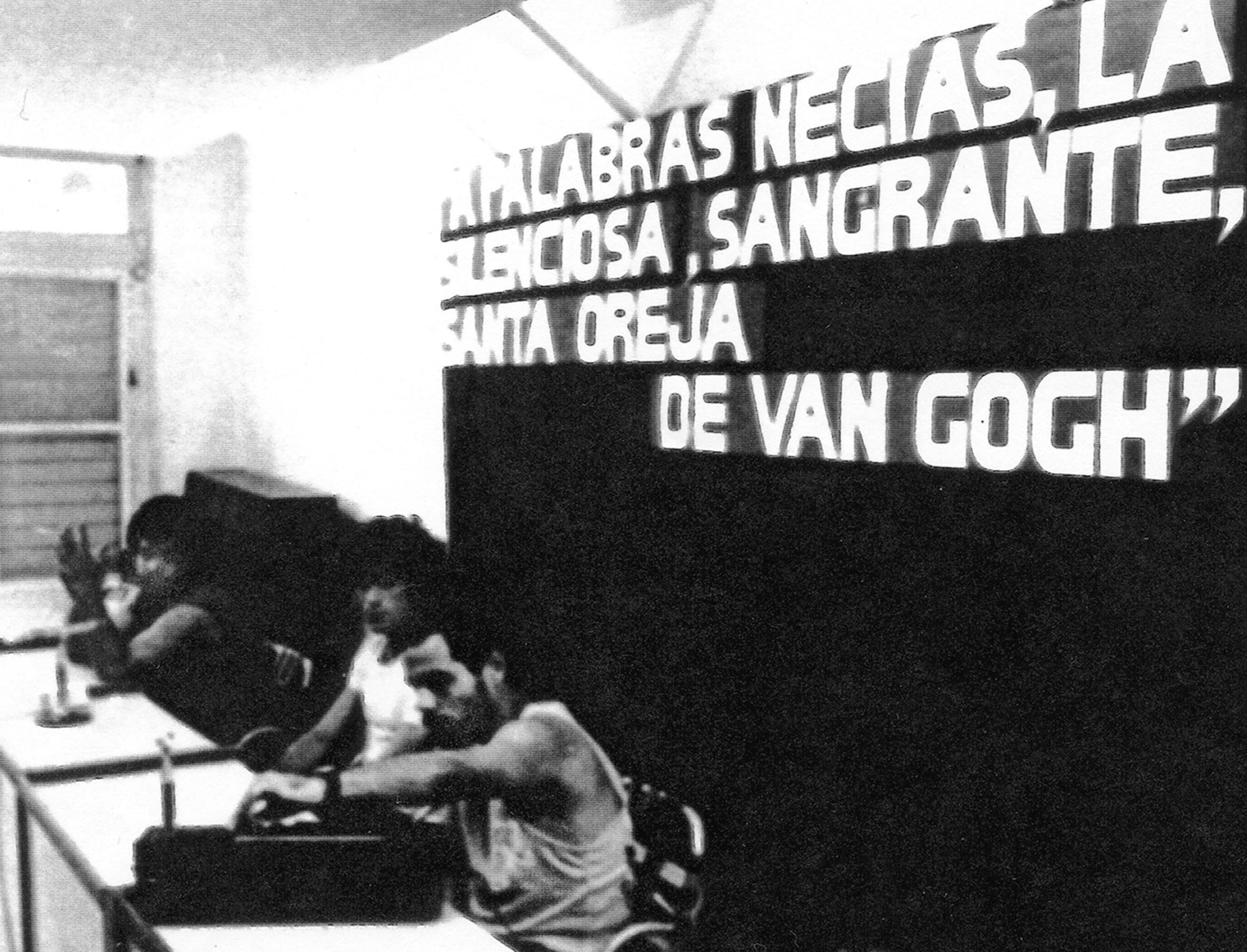

One of their final pieces, “La sagrada, sangrante, oreja de Van Goth,” took place in the institutional space, La Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba (UNEAC)[6]. In this case, there was a transition from general spectatorship to the State UNEAC functionaries being the exclusive spectator of Art-De’s action. The UNEAC invited Art-De to their building to create a dialogue and to raise the discussion about what their actions were provoking in relation to state institutions. The first time that Art-De’s discussion was programmed, a group of friends and followers of the artists appeared in the conference room. The UNEAC’s public servants canceled the meeting and rescheduled it to make sure that only people who were loyal to the state were present. The second time, González and Crespo prepared a performance. The room was decorated in the same style normally used by the Cuban Communist party during its meetings. In addition, they added a mirror with a golden frame, placed a microphone in the middle of the room and on the mirror they wrote: “If you have something to say, say it here.” The artists were the speakers, they were sitting in front of the public at a large table where they played a record of the national hymn and everyone stood up. Right then, Crespo took a hammer and broke the mirror located in the middle of the room. The action provoked a panic and the artists used the confusion to exit the room and closed the door from outside, leaving everyone locked in the conference room. Before the artists left the UNEAC, they put up posters in the grass that said “please, step on the grass.” After walking into the street, González and Crespo were arrested.

Soon after, Juan-Sí was forced into a political exile and Jorge Crespo went to prison for two years. After 30 years in exile, in February 2020, Juan-Sí González tried to give a talk about his work at INSTAR (Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt) located in Old Havana, but the political police prohibited him to leave his home and withheld his Cuban passport. Once again, the state prohibited a larger audience to follow his work. For Juan-Sí González, the goal of emancipating the spectator through participatory acts had been interrupted and the only community outside of state infrastructures that he was able to build are with those who tell his story.

Listening to a forgotten community.

In 2000, Henry Eric Hernandez along with the artists, Iván Basulto, Dull Janiell, Giselle Gómez, and Abel Oliva created the group Producciones Doboch without knowing about Art-De’s history. Henry Eric Hernandez and Producciones Doboch weren’t interested in the emancipation of the spectator; they wanted to learn about those narratives that had been outside of the state’s discourse, to hear out citizens instead of trying to emancipate them. Producciones Doboch was interested in producing collaborative and multidisciplinary interventions in order to create an archive of “minority” histories to challenge the official, national narrative.

As part of their art intervention entitled, Lampo sobre la runa (2000), Henry Eric Hernández and Producciones Doboch built a grave for Samuel Nisenbaum, one of the most respected majors in Old Havana’s synagogue. Jewish people who practiced their religion, similar to people practicing other religions, were socially segregated on the Cuban island.[7] It was prohibited to practice any religion after the Cuban revolution in 1959 (and continued until 1993) because communists are not supposed to have a religion. The artists started doing research on the Jewish cemetery located in Guanabacoa, Havana, as a starting point for their intervention as it was such a meaningful place for the Jewish community. A local worker showed them the place where Samuel Nisenbaum’s remains were buried in 1995, still without a tombstone marking the place.

The artists visited the Old Havana synagogue to which the Guanabacoa Jewish cemetery belonged to find out more about Nisenbaum’s history. There, Henry Eric Hernández was told about the immense importance of Nisenbaum for the community. At that moment, the Old Havana synagogue, in collaboration with Producciones Doboch, decided to build Samuel Nisenbaum a tomb. Hernández and Producciones Doboch carried out the construction of a marble and ceramic tomb. The inauguration of the tomb, as a conclusion of the process, produced an encounter between Nisenbaum’s family, the synagogue’s younger generations and the artists. It was both an opportunity to restore an important figure in this community and to commemorate the civil society that was rejected after the Cuban revolution. A small, but important moment of actual community building.

Cynicism.

In 2005, the artist Yunior Aguiar and I produced CDR 11, zona 10 en circulación – CDR Comité de Defensa de la Revolución (Revolution’s Defense Committee) – as part of a 2003 exhibition (Cátedra Arte de Conducta) initiated by Tania Bruguera. Without having heard about Art-De’s work or seeing an exhibition of Producciones Doboch/Henry Eric Hernández, we observed Cuban citizen’s strategies to deal with a rigid and unfair political and economic system and were inspired by it. Most of them didn’t confront the state with direct action; they tried to make the best out of the situation. This strategy implied that by behaving differently within these confines they held onto critical thought, both ideologically and ethically.

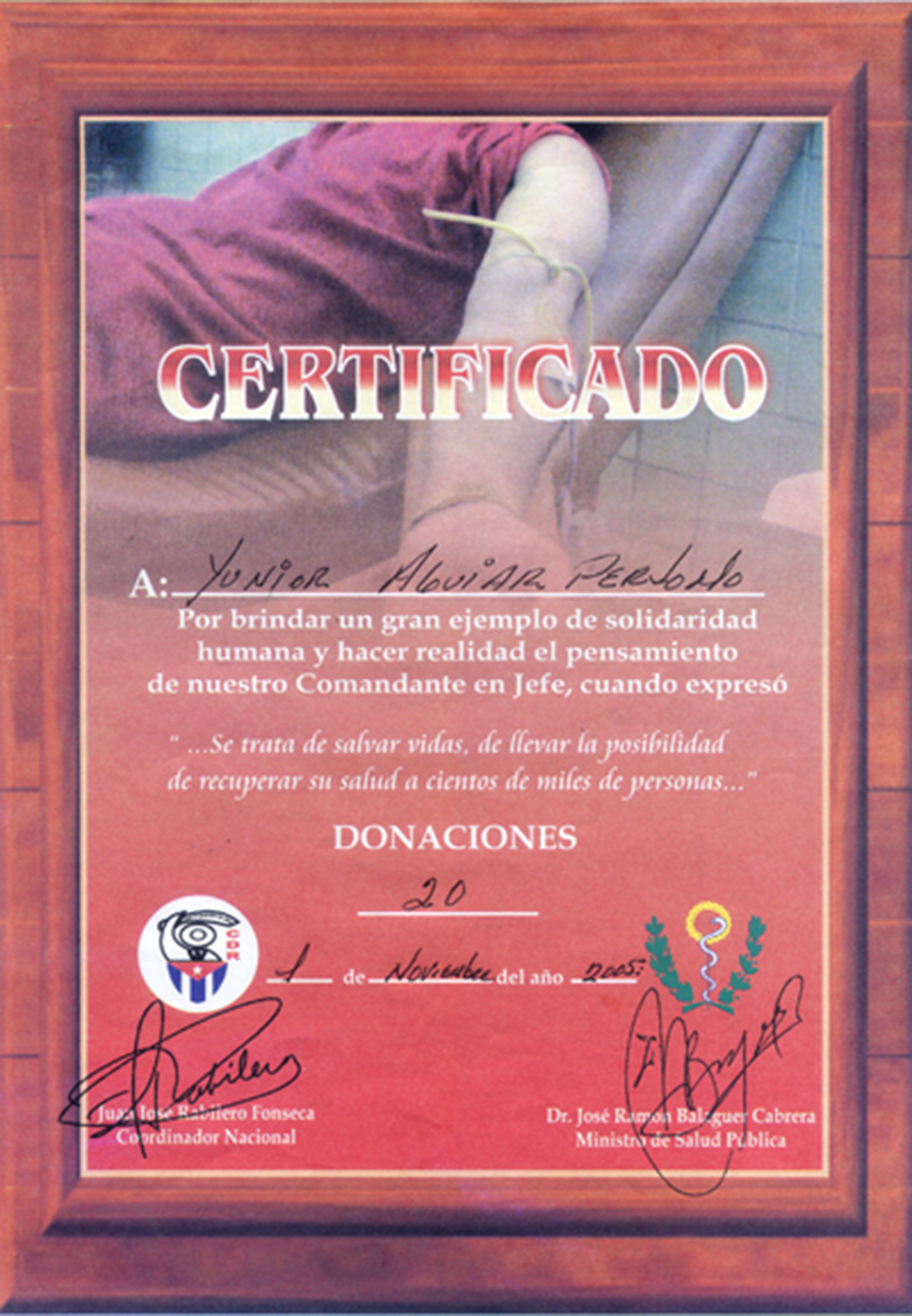

For CDR 11 zona 10 in circulation, we participated in a blood donation competition where every CDR had to take part.[8] The blood donation competition represented the solidarity of the revolutionary people, giving their blood for free. The block capable of collecting the most blood donations won the competition. In turn, people began selling their blood for as little as five dollars per donation. We used the same strategy to buy twenty blood donations and gave them to CDR 11, Zona 10 in order to compete in Yunior’s neighborhood. Buying the revolutionary solidarity and through the will of participation, we won the competition and Yunior Aguiar received a recognition with Fidel Castro’s words printed on it.

In CDR 11 zona 10 en circulación, we weren’t trying to emancipate the spectator nor were we calling for participation. Rather, we were adopting an opposing position as a mimetic strategy in a political context where participation was an obligation more than a civic right. Back then, spectators and citizens were not interested in building a community separate from state ideology, they were exposed only to the exceeding demand for participation and the huge gap between the economic situation and the state’s rhetoric. Ironically, in defying the possibility of community building, we formed one, if only momentarily.

MSI and 27N: The right to have rights.

On November 27, 2020, a large demonstration happened in front of the Ministry of Culture with visual artists, filmmakers, playwrights, actors, journalists, curators among others in the crowd addressing the question of the intellectual and art scene on the island. There were about three hundred people gathered by the end of the day. My colleagues and friends were there and the hundreds of Cubans who were not present were following the events through live transmissions that non-state journalists were broadcasting.

The protesters demanded freedom and civic rights for the San Isidro Movement (MSI) from the Ministry of Culture. A few days earlier, on November 18th, MSI members who were on hunger strike had been violently dislodged from the MSI headquarters by the political police, and some of them were arrested the night of November 26th, specifically the artist, Luis Manuel Otero. MSI members and other colleagues began a protest on November 22nd after rapper and singer, Denis Solis, was arrested on made-up charges. Denis Solis is a stigmatized Black musician who has written explicit lyrics against the state. The protesters decided to stay inside the MSI headquarters and half of the group started a hunger and thirst strike after the political police prohibited a public poetry lecture in support for political prisoners. Those gathered also demanded freedom of expression for artists, intellectuals and journalists, as well as halting the defamation of artists and activists on national television and the legalization of independent journalism.

After hours of waiting in the streets, the Vice Minister of Culture and other public servants accepted to meet with 30 of the protesters as representatives. While this meeting took place, the police surrounded the rest of the artists and intellectuals that were waiting outside, service was cut off and some political police dressed as civilians infiltrated the protest, trying to disturb the peaceful demonstration. More than three hundred people gathered, waited outside for many hours and began clapping every ten minutes to let the group of thirty people negotiating inside the Ministry know that they were still in the street, sitting on the pavement, accompanying them, but mostly, to let them know they were fine, the police hadn’t taken them away.

The attempted negotiation with the Ministry of Culture however turned out to be a failure. Less than 24 hours later, the National Television broadcasted the names of the protesters and members of MSI, which were shown as enemies of the revolution. After those events, a community of intellectuals and artists came together under the name, 27N.

On the eve of José Martí’s birthday, January 27th, some members of 27N decided to visit the national hero’s monument in Old Havana to leave some flowers and read poems. Some of the members never arrived as they were arrested after leaving their homes, including the artists, Camila Lobón and Tania Bruguera, poet Katherine Bisquet, and journalist Camila Acosta. In that moment, I was in Havana, I was already part of the 27N community, and I knew about the arrests through social media. A group of twenty people decided to gather in front of the Ministry of Culture, again, to demand freedom for the recent detainees. I joined in as it was an important and rare moment to come together.

The Vice Minister of Culture asked us to leave the street, twice. The third time, he asked us to enter the institution and we refused. Our presence in the public space was crucial to pressure the political police and achieve the liberation of 27N’s arrested members. We began to read aloud Jose Martí’s poem, “Dos Patrias,” and some minutes later, the Minister of Culture and a group of public servants came out and attacked an independent journalist in our group. Suddenly, the political police started to beat and arrest all of us, the street was blocked by police patrols and we were violently thrown into a bus which belonged to the political police.

***

Why has the art scene been so relevant for the civic emancipation of Cuba? In a country where creating a political party or any kind of civic association is illegal, the art scene is one of the few civic spaces with some autonomy. We don’t work in an official institution to make art and we don’t depend on the state to produce our artwork or gather as a group. These collective actions do not seek to engage with the question of authorship, but rather create a confrontational situation. The hunger strike, clapping in the street and reading poems aloud can be understood as artistic actions, despite their civic goals. Despite this, today, a year later, most of the members of MSI or 27N are abroad due to the state’s repression and the artist, Luis Manuel Otero, the singer/musician, Maykel Osorbo, and the journalist, Esteban Rodriguez, are still in prison. The attempt to build a community was, once again, frustrated by the state. Nonetheless, we are building it through gatherings such as the New Alphabet School’s Community Building edition and through the various efforts I recounted in this text. With this text, I call out to those isolated in their protest: you are not alone!

[1]My generation is not of a specific age, it includes people born in the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s. The main referents to define a generation are political events.

[2] In 2021, the visual artist, Hamlet Lavastida, and the poet, Katherine Bisquet, suffered a forced exile. The same happened with the art historian and activist, Caroline Barrero in February 2022. The visual artist, Luis Manuel Otero, has been imprisoned since July 2021 and the rap artist, Maykel Osorbo, since April 2021. January 27th, April 5th, and July 11th of 2021 mark the most relevant public demonstrations in Cuba and were violently repressed by the political police. From January 2022, the state declared around 700 citizens as guilty for demonstrating on July 11th against the state. The sentences range from 5 to 23 years in prison.

[3] For example, every political demonstration had been organized by the state from the beginning of the revolution (1959) and to participate in them has been obligatory for all citizens. The citizens who decide not to participate in a political event are considered counterrevolutionary. A counterrevolutionary, in state rhetoric, is equal to supporting imperialism, and therefore those people do not deserve to have a job or study at the university.

[4] The anthropologists include: Marcus G. and Myers, F., eds. (1995), Marcus, G. (2010), Elhaik, T. (2013) Schneider, A. and Wright, C. (eds.) (2006, 2010, 2013, 2017) Sansi, R. (ed.) (2016) and from the art field: Bishop, C. (2006), Bishop, C. (2012), Bourriaud, N. (2002), Kester, G. (2009), Kester, G. (2015), Foster, H. (1996), among others.

[5] Cuba and the U.S. started diplomatic relations for the first time since the Revolution during Barack Obama’s presidency. This situation brought economic hope to Cuban citizens, a boom in the Cuban art market and attention from the international art scene. Artists and intellectuals that left the country decades ago came back to the island hopeful to see political and economic change.

[6] La Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba (UNEAC) was founded in 1961 before the Cuban revolution. It is an ONG that has the goal of bringing together the most important artists and writers of the country. Nevertheless, the UNEAC has been following the state policies since its creation. It has been complicit in the censorship and repression of Cuban intellectuals during the last decades.

[7]By socially segregated I refer to social death: if a citizen insisted on practicing a religion – Afrocuban, Christian or Jewish religions – or demonstrated their affiliation to one by, for example, wearing a symbol on their clothes, they were unable to have a social life, get a job or study at a university. People maintained their religious practices from 1959 to 1993.

[8] Cuban people are required to be a part of a state organization – referred to by the state as “organizaciones de masa.” Some of them are: “Comité de Defensa de la Revolución” (CDR) to organize every neighborhood, “Federación de Mujeres Cubanas” (FMC) which every women must be a part of, “Organización de Pioneros José Martí” (OPJM) which all primary school students must be a part of (and there are branches for high school and university students as well), and “Central de Trabajadores de Cuba” (CTC), which every worker must to be a part of.