The multiple spatialities of City Plaza: from the body to the globe

The discussion among the “Initiative of Solidarity to Economic and Political Refugees” – a grassroots coalition of groups of the radical Left in Athens – to create a large scale housing squat for refugees started in September 2015. It was a period when thousands of refugees were gradually arriving to the mainland of Greece from the Aegean islands. At the time, the European authorities named it a “refugee crisis” while for refugees themselves and also for the antiracist movements all over Europe it was the “summer of migration”(Kasparek and Speer 2015). During these first months, refugees were in transit through Athens, as they would stop there for a few nights and then would continue their travel through Eidomeni to the Balkan route in order to arrive in one of the Northern European countries to settle. This transit movement was transforming different public urban spaces into informal and temporary shelters, so the assembly of the initiative decided not to focus on one building but to extend the solidarity throughout the city. For these first months there were daily ad hoc interventions in temporary spaces – from Victoria to Omonoia and Pedio Areos – where food, basic items like tents, blankets and clothes, but also medical care was offered to those in need.

The decision to squat City Plaza was taken a few months later, when the EU-Turkey deal was signed, on 18th of March 2016. A deal that marked the definite end of the “summer of migration” and also the final closing of the Balkan route, leaving more than 60.000 migrants trapped in mainland Greece, and thereby transforming the Aegean islands into a buffer zone or a double border between Greece and Turkey (Mezzadra 2018). It was this moment when hundreds of people were homeless in the center of Athens or living in remote refugee camps in harsh conditions, while borders were reinforced once more. When the solidarity movements were then also increasingly illegalized in dominant policies and discourses, we decided to create a large scale housing squat in the center of the city. A squat that would not just be a housing project but a continuous political struggle claiming co-habitation in the center of the city against the migration policies that promote the social and spatial exclusion of the “camp”, a counter example of solidarity against the multiple borders and institutional racism that proliferate in Europe.

After a month of intensive preparations, on 22nd of April, City Plaza was squatted. The choice of the building was based on two main parameters:. The first one was the morphology of the building and the second one was the neighborhood in which it was located.

The morphology of the building

The squat aimed at creating a shelter that would function as a counter-example in the city space, offering dignified conditions of housing to those that it could host. In this perspective, we rejected public buildings that used to function as offices or schools and could not offer any kind of privacy to people that would inhabit them. In the case of City Plaza, the hotel structure could offer a more appropriate shelter: with rooms that had a door that closed, a bathroom, a wardrobe, a small balcony – simple things that are taken for granted to those of us who live in a house, but which are not at all granted to people who have been on the road for months or even years. City Plaza is an eight-storied building with 126 rooms. Around 100 of these rooms were transformed into small houses for refugee families or shared by either single men or women. About 20 rooms were shared between people from the solidarity group, mainly those coming from abroad to support the project and also some locals. The remaining rooms were transformed into classrooms, storages and a woman space. At each period around 350-400 refugees and 30-40 solidarity activists would share the rooms of City Plaza, transforming the space not into a shelter for migrants but into a space of co-habitation and sharing. In the 39 months that City Plaza was open and active, it hosted more than 2.500 refugees.

Furthermore, the morphology of the hotel also included common spaces. On the ground floor there was the reception and some smaller office spaces that were converted into a clinic, a room with computers, meeting spaces, and a room that was used ad hoc as a makeshift barber shop, dentist clinic, clothes bazaar, ping pong room or space for meetings of thematic groups. There was also a small yard that was used as a children space, where bicycle workshops took place and which served as a meeting space.

On the first floor there was a bar, a meeting space that was transformed into a playing room for children, a kitchen where the food was prepared three times per day and a dining room which was also used as a space for the house assemblies and a space for celebrations and parties.

Through everyday uses, the morphology of the hotel was transformed into a peculiar village. With houses and neighborhoods on every floor, a makeshift café, a restaurant, a clinic, classrooms, assembly spaces etc. This village was peculiar not only because of its vertical structure in an eight-storied hotel but also because of its residents. Refugees coming from more or less 10 different countries, not speaking the same language, having different social, cultural, economic and political backgrounds and also different plans and aspirations for their future. In addition the solidarity group that was not only from Athens but also from many other countries around the world, had similarly different backgrounds, motives and practices.

Neighbourhood

The second parameter that played a crucial role in selecting City Plaza was its location. On the one hand, City Plaza was located next to Victoria square, one of the squares in the city that became a hub for transit migrants and after the summer of 2015 many times was transformed into an informal shelter. Located also next to Agios Panteleimonas Square and a neighbourhood where during 2008-2013, the fascist group of Golden Dawn was systematically attacking everyone who looked like a “stranger”(Kandylis and Kavoulakos 2011). In this neighborhood, the electoral percentages of Golden Dawn were much higher in relation to other Athenian neighborhoods, indicating a social acceptance of the fascist discourse and practices. Thus, in this neighborhood we decided that it was really crucial to intervene with an organized political space; since the aim of the squat was not only to create a safe house for refugees but also a hub of political intervention – from the smallest scale of the neighbourhood and the city to the national and transnational policies and strategies that illegalize migration and construct deadly borders for poor residents of the Global South.

The first contact with the neighbourhood was really challenging. The first day of the squat, in the narrow Katrivanou street where the entrance of the hotel was located, most of the neighbors had initially a really aggressive attitude: they were shouting, throwing water from the balconies, threatening to call the police and the Golden Dawn to evict the squat. As time passed, this aggressive attitude shifted. In the first days of the squat some work was done to improve the outdoor space. The broken flower boxes were repaired and plants were seeded, while we changed the broken bulbs so there was light in the street. For the safety of the squat, we installed 24 hour protection shifts from the first day to the last. If, in the first day of the squat the neighbors thought of City Plaza as a space that would create problems and further insecurity in an already downgraded part of the city, it gradually became evident that the squat brought livelihood and also increased the feeling of safety as a result of the daily presence and the organization of the space.

Gradually, some of the neighbors started bringing donations to cover the needs of the residents of City Plaza and participated in the open events and celebrations that we held in the squat or in the neighbourhood. In many occasions people from the squat also provided for the neighbors when it was possible: a small technical assistance in a house in need, helping older neighbors, or providing medication from the clinic to someone in need. Of course there were also tensions – mainly due to the noise from the squat – however these were inscribed in the context of neighborhood relations.

Creating a common space

As much as the choice of City Plaza was based on more abstract characteristics of space such as the morphology of the building and the social and political characteristics of the neighborhood surrounding it, what really made City Plaza into what it was, were the social relations that were manufactured within it. And these relations were not created automatically, just because 400 people were living in one building which met certain requirements. These relations were created gradually, through hard daily collective work, through hours of assemblies and meetings, through a lot of thinking and critical reflection, always in respect to the experiences and needs of different people. Far from romanticizing solidarity projects, at Plaza it was proven once more that self-organization presupposes structures, collectivity and organization.

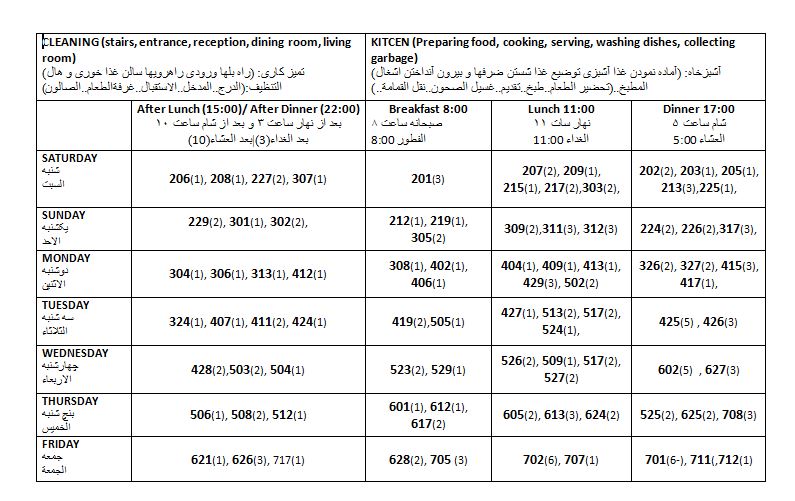

One of the main decisions taken in the project was that everyone had to participate in order to make the space work. Through trial and error and after several long discussions we came up with a system according to which the adults of each room had to undertake one shift per week for 3-4 hours for cooking, washing dishes or cleaning the building. These shifts were internally distributed not following the principle that “we are all equal” but “to each according to their needs, each according to their abilities”. For example, cleaning and building maintenance was a heavier task, and thus it was mainly undertaken by single men, while the breakfast shift, which was relatively quick and easy to do, was taken up by single mothers. Certain elderly people or people with serious health problems were excluded from shifts.

Engaging everyone in the project was not just a practical choice in order to get the work done. It was first and foremost a political choice. It was a choice against the relationships of dependency created in most official structures where refugees were simply left to queue for food, for clothes or expect services. Taking part in the everyday work of Plaza meant that refugees were not just treated as vulnerable or as victims, but as members of an active community with certain responsibilities and obligations. This meaningful participation and cooperation created conditions in which people gradually stopped feeling helpless or victimized; they were the ones to support others, to undertake various responsibilities, to provide care for their community and their space. Henri Lefebvre wrote in 1968 that everyday life is not only about tedious tasks and preoccupations with bare necessities, but also a realm of emancipation (Lefebvre 1990). Furthermore, the role of the local solidarity group and the commitment to making City Plaza work was also fundamental. Against the impersonal and distancing relations among refugees and the employees of a state structure or an NGO, both local and international activists who participated in City Plaza were committed, many were living inside the building, devoting a lot of time and energy, taking responsibilities and risks. As Arundhati Roy put it: “The NGO-ization of politics threatens to turn resistance into a well-mannered, reasonable, salaried, 9-to-5 job. With a few perks thrown in. Real resistance has real consequences. And no salary.” (Roy 2016:335). For all of the people living in City Plaza this process of participation and sharing responsibility – often a very big one – was a process of political and social emancipation. Relationships of dependency were, in a way, transformed into relationships of interdependency, care and cooperation within a community.

Nonetheless participation was not limited to sharing the everyday chores but also to decision making. House assemblies, coordination meetings, working meetings of the different groups (e.g. reception, kitchen, woman space, children activities et,) were taking place daily in City Plaza. To ensure participation of everyone was certainly a critical stake and at the same time quite a difficult and complicated process (for more see Lafazani 2018). In the first House Assemblies certain ground rules were decided. These rules were actually coded in three axes. The first one was that we solve our problems with dialogue and common understanding and not with fighting or violence. The second one was that we don’t drink alcohol inside the building as everyone can go out whenever they want to have a beer in a square or a bar – a rule that also aimed at avoiding fights. The third one was that we respect the building and all the other people who live there. The crucial question, however, is why did all these different people who lived for shorter or longer periods in City Plaza, from refugees to solidarity activists, a total of more than 3.000 in the 39 months the squat operated, abide to these rules? In the refugee camps or other institutional shelters for example, similar rules are in place but still there are serious fights and incidents of violence. It seems that the reason people respected the rules was the sense of community, of respect and trust, a sense of participating in the creation of a common space, a sense of belonging to this peculiar village. And these relations that were built in the common everyday life, were built through the ways we cooperated and spoke to each other, through the ways we cared for each other’s needs and wishes.

From the building back to the city: the streets belong to us

Plaza was not an enclave and a community looking only on the inside. On the contrary it was an active part of several social and political movements in the city and beyond. Plaza entailed a “double movement”. On the one hand it produced rights inside the community for people socially and politically categorized as undeserving: it provided housing, food, medical care, education to people that could not access those rights through institutional structures. On the other hand, wider claims were articulated around the right to have rights.

First and foremost, our struggles were targeted around freedom of movement and the right to settle. Through exemplary struggles, the Plaza community attempted to create cracks in the institutional spaces for the participation of refugees. An example of such a struggle was the attempt, together with radical teacher unions, to enroll all children of City Plaza in public schools, although according to the Ministry of Education the refugee children should only get schooling in the camps or in separate afternoon classes. From the first year until the last, all the children participated in the classes together with the local children, a fact that opened up this possibility to many more refugee children.

Moreover, City Plaza community called for and participated in many actions and demonstrations, both local and transnational, during all those years. Whether it was contesting the policies of closed borders or protesting against the EU Turkey deal, or demanding the closing of refugee camps and the opening of empty buildings in the city for refugee accommodation, City Plaza community articulated numerous different claims around freedom of movement and the right to settle (for more on the struggles initiated by City Plaza see Kotronaki 2018).

Nonetheless, the Plaza community not only participated or generated struggles around refugee rights but also took part in wider mobilizations of the antagonistic movement. It took part in demonstrations around labor rights, around the rights to public health and housing, and also in antifascist actions. These moments of common struggle also formed different relations among the inhabitants of City Plaza. In such moments, it became even more obvious that we all stand together against the prevailing policies.

Lastly, Plaza would organize and/or participate in different events in the city: organizing open discussions and celebrations in the neighbourhood or participating in festivals and other political events throughout the city.

In many different ways, City Plaza intervened in the urban fabric: either by the very act of occupying the building and transforming it into a different home or by occupying the streets and squares of the city, generating common struggles and creating common spaces.

From the body to the globe

At the same time, City Plaza also had a global scope. Not only because in one building people from many different countries coexisted, bringing into the everyday life the richness of experiences from all over the world. But mainly because it manufactured a struggle in multiple and interlocking scales: from the body to the globe.

In Plaza, the most trivial, the most everyday and tedious tasks became political: how we cook the food, how we clean the building, how we take care of children, how we share resources and responsibilities, how we speak to each other. This scale, the scale of everyday social reproduction – often invisible in political discourses and hidden in the private realm of the house – in City Plaza was overly visible: it not only had to be framed, but became a main theme of discussion in assemblies and meetings, it became a basis for a different starting point of “being political”.

Οn the other end, City Plaza managed to exist due to transnational solidarity. From all over the world, from Germany to China, from the States to Switzerland, from Mexico to Turkey, different autonomous groups and collectives were supporting the maintenance of Plaza: either by donations, by political support or by physical presence. City Plaza would have never managed to exist without this crucial global support.

From the production of a common space in the everyday life to the global solidarity there was a multi-scale process of creating a transnational community of struggle against the policies that manage “flows” of people on the one hand and the industry of “aid” projects by NGOs on the other. However, the creation of a community of struggle is not an abstract claim but a result of political action. Certain initiatives and projects take place within conditions of harsh inequality, partitioning of rights, and antagonisms between the oppressed. These contradictions cannot be eliminated in a single building – no matter how much will or effort is put into it. In other words, there are no “islands of freedom” within the wider relations of exploitation and domination, within the world of capital and the state (Lafazani 2017). Against romanticizing on the one hand and victimization or fostering relations of dependency on the other, in City Plaza, collectivity, cooperation and self-organization were manufactured step by step and through many problems and conflicts in the everyday life.

In light of this, the political goal of City Plaza was also global in reach. Not only arguing against racism, sexism, colonialism, exploitation and multiple borders but proving, through a day-to-day struggle, that we can start to dismantle them.

References

Kandylis G and Kavoulakos K I (2011) “Framing urban inequalities: Racist mobilization against immigrants in Athens.” ΕπιθεώρησηΚοινωνικώνΕρευνών 136(136):157–176

Kasparek B and Speer M (2015) “Of hope: Hungary and the long summer of migration.” Bordering.eu. https://bordermonitoring.eu/ungarn/2015/09/of-hope-en/ (last accessed 03 March 2020)

Kotronaki L. (2018) “Outside the Doors: Refugee Accommodation Squats and Heterotopy Politics.” South Atlantic Quarterly 117(4):914–924

Lafazani O. (2017) “1.5 year City Plaza: A project on the antipodes of bordering and control policies.” AntipodeOnline. org. https://antipodeonline.org/2017/11/13/intervention-city-plaza/ (last accessed 09 June 2021)

Lafazani O. (2018) Homeplace Plaza: Challenging the Border between Host and Hosted. South Atlantic Quarterly 117(4):896–904

Lefebvre H. (1990) Everyday life in the modern world. New Brunswick: Transaction Books

Mezzadra S (2018) In the Wake of the Greek Spring and the Summer of Migration. South Atlantic Quarterly 117(4):925–933

Roy A (2016) The end of imagination. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books