WHOLE WORLD

A malleable sac swells and sinks repeatedly. Sinewy, rubbery and vacuous. It rises, alive with the possibilities of expansion but soon deflates as the invisible molecules holding it up make a hurried, restless exit to become one with the ether. This return of the air to its unavailing crucibles can be a metaphor for life itself. What is the ‘W(hole) W(o)r(ld)’? An incomplete repetition? A leaky gap that always lets more out than in? A rhythm that relentlessly swings between capture and concession?

W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D

W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D W H O L E W O R L D

/dum/dmm/dam/: دم

noun

breath, existence: سانس ، ہستی

/hasti/,/saans/

beingness, (living)entity: وجود ، ذات

/zaat/,/wajood/

mediator, moment: طفیل ، لمحہ

/lamha/, /tufail/

Simultaneously the pinnacle and the brink, the Persian lexical morpheme دم denotes the fragile border between life and death. It is the sign of life in a body, lasting for the duration of a breath that is precariously dependent on the next inhale of air into the body to be transformed into breath, to extend the pulsating energy of one lived moment to the next. This inherent act has repeatedly been politicized over human history by forcefully constricting pathways of wind for breathing and existing within, altering it to a conscious act that lies in a precarious balance. Recent times of war and global pandemic witness an increased loss of this equilibrium due to the hierarchies of power and capital – social, political, and economic, that constrict breathing for those placed in the lowest order by threatening and rationing the basic and most crucial right to existence.

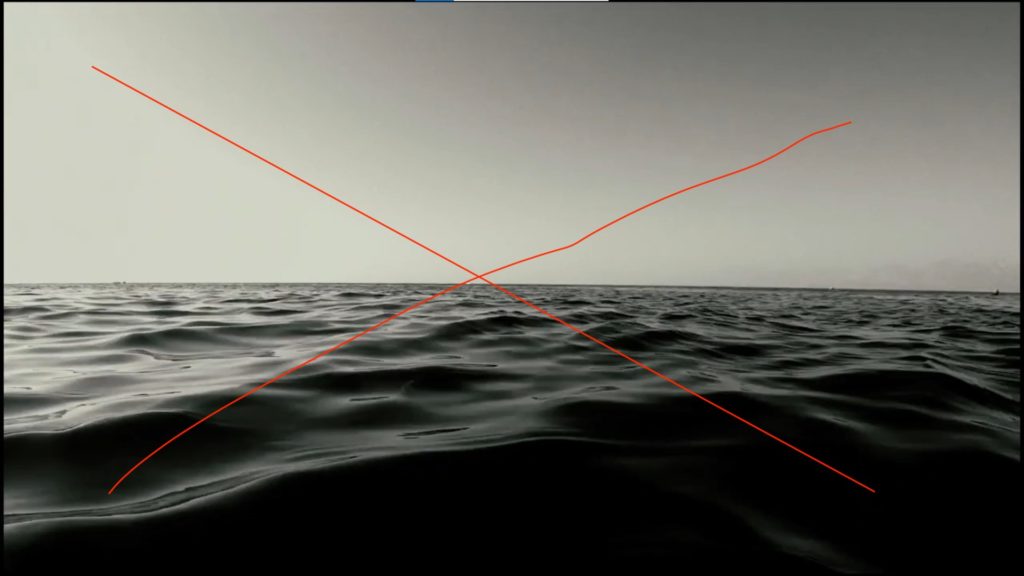

What does it mean to attend to the gap between the world and its image with care and precision? Why must it be done?

Do not Look, Do not Touch, تھیلا

(TAKE THEM AWAY IN FAITH)

رحم

It is difficult to think of anything else but ‘breath’ in our post-pandemic contemporary. It is, however, equally impossible to think of any time or moment in the history of our shared world, without thinking of this most fundamental act of claiming life. To breathe is to avow the élan vital. The time of a ‘breath’ is a conceptual and corporeo-political duree. Under the shadow of the Covid-19 pandemic that has arguably altered the world forever, the breath is faced with new challenges and has also assumed a new enunciation. This intimate bodily sensation has become the arena of collective rage against police brutality – “I can’t breathe”; the grief of thousands losing loved ones to a manufactured oxygen scarcity and the beauty of those who have been resisting onslaughts on hard fought expanses. This short and felt interval has come to encapsulate nothing less than the whole world.

For the act of filming too, the breath poses a unique challenge. How does one produce an image for something that is present but invisible? The chasm between sensation and representation becomes instantly perceptible. The unrepresentability of the breath swells further as it weaves across the biological, cultural and political body- simultaneously material and etheric. The split second of the breath is also a splitting of the osmotic edges of cinema. These edges find themselves drenched today in an explosion of unauthored image fragments circulating feverishly on social media, cinematic memories of times past, the urgency of documentation, the necessity of erasure and the inevitability of a lag between the lived and the felt. In this climate when images are heaving, the film edit straddles the delicate boundary between inspiration (breathing in) and expiration (breathing out). To truncate or extend filmic time is now layered with echoes of life, imagination, disappearance and death.

This time can also be invoked by the presence of human and extra human protagonists who can help us draw lines in the air. Whose traces aren’t byproducts of loss and erosion but the kernel of those to come. These are productive contaminants of a recrudescent world. They appear and fade just as air, making us all etheric in their wake. Perhaps there has hardly been a time where the eupnoea of the filmic and that of the world, has come to stand in for one another. It is to this coalesced time that we owe our exploration. We urge you to read what follows as breath acts, episodes that house the implosions, promises, betrayals and desires of the contemporary. Through a piecing together of these interludes, a vital weave of the ‘now’ will be secured.

Proposition One: Sewer as a breath analyzer

Jai Hind, Jai Valmiki !

I’m a sanitation worker. I live in Dallupura. My name is Mahipal.

The bigger sewers are scary. Accidents happen often. We have lost a few co-workers too.

We do not know if they were paid adequate compensation by the authorities.

Sewers are packed with toxic gases. We check up on our mate every 5 mins, after we lower them into the sewer.

Some sewer lines are very broad with a heavy water flow. Often a sewer looks bigger on the surface but as you step in it gets really narrow and cramped. The probability of drowning in them is very high.

We once went to clean a sewage line in Noida. We lost a co-worker there because he couldn’t breath due to the toxic gases. It was a particularly poisonous sewer because it hadn’t been opened in a long time.

Before going in we check the depth of the sewer with a rope. We then tie a rope around our waist. Two people help us climb down into the sewer. They slowly keep lowering the rope till we reach the bottom of the manhole. We signal to our co-workers outside that we are safe.

Then we clean the wet and dry waste of the sewer. If we start running out breath, we are immediately pulled up. After coming up we sit for a while, drink some water. At times, during summer, our colleagues even fan us while we catch our breath.

There is all kinds of waste in the manhole from urine, faeces to torn clothes. We often find insects like cockroaches and scorpions inside the sewer line. It is scary. There’s always an urge to finish work as quickly as possible, go back home and take a shower.

We take a bucket down with us to clean the sludge. We fill the buckets with sludge and send it up. Many times it also fall on us from the bucket. It’s an icky feeling. I feel nauseous.

It’s a really tough job.

Sometimes I feel like I want to run away from all this. It feels filthy being covered in urine and faeces.

When the lid of a sewer is opened it emits a strong smell. The toxic gases make us feel ill. We keep the sewer open to release the gases before we go in.

Our skin itches due to the toxins. It lasts for about 2-3 days. When bathing doesn’t help we have to visit a doctor.

Our feet get wounded, from the glass, from iron rods. We get infections because we work in that filth and have to visit doctors frequently.

We are doing this work because of our caste. We have been labelled as low castes. Many people treat us like untouchables. They don’t allow us to stand in their vicinity. This discrimination has been going on for ages.

We were poor and couldn’t afford an education but we still need to bring up our kids. So we do this work. Our managers often tell us that it’s our duty to do this work. They don’t care whether we are able to breathe or not.

They don’t even consider us human or try to understand our issues.

We feel scared for our life. Working in this filth can cause problems in our liver, our lungs. We fear getting a chronic disease like tuberculosis. We do this work out of compulsion and lack of other options.

Our people have been doing this work for ages now. We aspire for a time when our kids won’t have to do this work. Our future generations don’t have to suffer from all this. We shouldn’t be doing this work because we belong to lower caste. If our kids get education they can do better things.

My parents were very poor they couldn’t afford an education for me.

In our village there wasn’t a proper job system. People who owned land, earned out of it. The others did odd jobs like picking up garbage and cleaning sewers to survive.

Now I feel my people should grow. We should educate our children. Give them a respectable life. Caste discrimination is a man made concept. We are all one in the eyes of god.

Our government introduced these new sewage cleaning machines. They are a total sham. These machines malfunction in a month or two and then poor people like us are hassled again.

We want these cleaning machines to work. We want them to clean the sewers so that we don’t have to do this dirty job.

There are massive administrative issues. I’m a sanitation worker in Noida. We went to pick up garbage from sector 7 this morning. We were attacked. One of our co-worker got injured. We went to the nearby police station but there was no justice. Justice for lower caste people is very hard to come by.

We want to be treated as equals. Even the government doesn’t pay any heed to us. Sanitation workers are looked down upon because of the nature of our work.

The ‘W(hole) W(o)r(ld)’ conditionally allows concessions to greater access to life, respectability, and humanity dependent on socially imposed and reinforced identitarian facades. Here the effort of pulling air into the lungs to sustain breath is synonymous to the consistent struggle for survival against caste and racial violence, police brutality, oppressive regimes, failing systems of care, class asymmetries, and the climate crisis. Yet it is the duration of each breath and the duration between consequent breathing that denotes beingness and marks the moment of existence. And we ask as we witness and experience the restrictions, how can the duration of each breath be extended such that the echoes of life can be heard and recognized?

Proposition Two: A Dialogue with Hippocrates

“Wind in bodies is called breath, outside

bodies it is called air. It is the most powerful

of all [the three kinds of nourishments, namely, food, drink and wind] and in all,

and it is worth while examining its power.

A breeze is a flowing and a current of air.

When therefore much air flows violently,

trees are torn up by the force of the wind,

the sea swells into waves, and vessels of

vast bulk are tossed about. Such then is the

power that it has . . . but it is invisible to

sight, though visible to reason. For what

can take place without it. In what is it

not present? What does it not accompany?

For everything between earth and heaven is

full of wind. Wind is the cause of both

winter and summer . . . wind is food for

fire, and without air fire could not live . . .

“How air, then, is strong … has been

said; and for mortals too this is the cause

of life, and the cause of disease in the sick.

So great is the need for wind for all bodies

that while a man can be deprived of every..

thing else, both food and drink, for two,

three or more days, and live, yet if the

wind (air) passages into the body be cut

off he will die in a brief part of a day,

showing that the greatest need for a hody

is wind. Moreover, all other activities of

man are intermittent, for life is full of

changes; but breathing is continuous for

all mortal creatures, inspiration and ex..

piration being alternate. . . . After this,

I must say that it is likely that maladies

occur from this source and from no other.”

(Quoted from W.H. S Jones’ translation [1923-31]

Proposition Three: Ash

Hundreds of bodies were being cremated every day in the city of Delhi through March and April 2021- even more lay in piles as crematoriums and graveyards had run out of space. The ash from the pyres that burned through the night rose into the air and landed softly on terraces, on cars, in playgrounds by dawn. We who were still alive had now begun to inhale the dead. This ingestion of pain, suffering and death also brought with it a collapse of language. Untimely and abrupt departures of loved ones, the humiliation of not being able to say goodbye, the medicalization of conversations, the anxious reduction of life to oxygen readings and CT images – all this lacerates words. Sentences bleed out and gasp for breath just like thousands of Indians – from whose lungs air was thieved. Breathing is no longer a function, it is an act.

Proposition Four: Can we lie close together for a bit?

My name is Mohammad Chand. I’m the grave keeper at graveyard near Maulana Azad hospital.

This is a private graveyard.

There aren’t many burials here.

At best 8 to 10 in a month.

But the months of April and May 2021 were very grim.

We were struggling to prepare the graves while the bodies kept piling up.

It felt like an apocalypse. Maybe God was expressing his displeasure.

We were under extreme duress.

We had to open older graves and bury new bodies in them.

The carousel was unceasing. We couldn’t leave the departed unburied.

It was a very tough time. We kept praying to the almighty to show some mercy..

..but who knows what his plans are.

There is a Waqf board operated graveyard near ITO. During April and May last year, there were 40-50 burials a day on an average. They also faced an acute labour shortage and often called me for help. They were using an earth mover to dig graves. The numbers were large there because the people would come from all over.

We were performing 3-4 burials a day instead of 8-10 burials in a month during normal times. We don’t perform as many burials here but that one month saw 90 burials. We were quite worried about what to do. The graveyards are filled to capacity. We were tossing and turning the older graves around. We were burying bodies over bodies.

That’s about it.

We have an acquaintance in old Delhi, Moinuddin. He died of the virus at Lady Harding Hopsital. He had to be taken to the graveyard at Delhi Gate. His body was kept at the mortuary nearby.

There was also another Moinuddin from Seelampur who died at the same time. The was a mix up at the mortuary. When people from Old Delhi came to receive the body they insisted on seeing its face. When they saw the face they realised this was not their brother. So it often happened during that time, bodies got mixed up and nobody knew who they were burying.

Eventually the people from Seelampur were called and the right body was handed over.

The issue was resolved and both Moinuddins reached their assigned resting place.

People were afraid to look at the faces of their own Corona deceased relatives.

We were told to not touch the bodies, not pray around them.

The graveyard at Delhi gate is massive. They can afford to cordon off an area for Covid burials. Space is a huge factor here. We won’t dig for at least 20 years around the bodies of the Covid deceased. We won’t even consider that place for non- Covid burials.

TAKE THEM AWAY IN FAITH

قیامت

TAKE THEM AWAY IN FAITH

ناراز، دکت ،الٹا پالٹی، گھبراہٹ ، پریشان

TAKE THEM AWAY IN FAITH

قبرستان، بڑی جگہ، پہلا نیوالا ، سیوا

TAKE THEM AWAY IN FAITH

دکھ، پورا پریوار، ۹ مہینے کا بچہ، ایک سے ڈیڑ گھنٹا ,PPE Kit

TAKE THEM AWAY IN FAITH

Each day they renew ancient bonds,

Ancient bonds that hold fast

Binding our lot to their law,

To the will of the spirits stronger than we

To the spell of our dead who are not really dead.

Whose covenant binds us to life,

Whose authority binds to their will,

The will of the spirits that stir

In the bed of the river, on the banks of the river,

The breathing of spirits

Who moan in the rocks and weep in the grasses.

Spirits inhabit

The darkness that lightens, the darkness that darkens,

The quivering tree, the murmuring wood,

The water that runs and the water that sleeps:

Spirits much stronger than we,

The breathing of the dead who are not really dead,

Of the dead who are not really gone,

Of the dead now no more in the earth.

-Birago Diop, (excerpt from) Spirits.

Proposition Five

Ours is perhaps the perfect love story because time spins itself painlessly around us

Joseph Wright ‘of Derby’ An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump 1768 Oil on canvas, 183 × 244 cm Presented by Edward Tyrrell, 1863 NG725 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/NG725

This 1768 painting by Joseph Wright of Derby produces an image for the ‘absence’ of air. The thin line between air and breath- outside and inside is conjured. The bird in the painting is dying slowly as the air pump (Robert Boyle’s discovery) creates a vacuum in the glass case in which it is held. This slow disappearance of air and breath evokes a mixture of terror, fascination, curiosity and grief from those who look on. The theatre of everything and nothing.

Breath as a verb is a political act in the ‘(w)hole (w)orld’ against the suffocation and usurpation of breath experienced and witnessed across geographies and temporalities. It is a consciousness- an awareness of being, of the self and other breathing bodies in the surrounding – a recognition of the needs and values for the self and the collective. In his poem Desperate Age, Tenzin Tsundue writes,

Within the prison

this body is yours.

But within the body

my belief is only mine.

Proposition Six

An Obituary is a memory device. A public commemoration of a life lived. It is antithetical to statistical figures of death that abstract people into cases or quantities. An obituary insists on details. What mattered to the departed? Who did they matter to? And people who mourn them. Since the Covid-19 pandemic began obituaries pages across newspapers and websites have swelled monstrously. Accounts of lives and achievements, names of children, pets, parents and spouses, descriptions of friendships and careers tumble into our everyday via the dead. There is however a discrepancy, many statistics don’t lodge these abrupt departures as pandemic deaths. The regime of numbers repudiates the labour of mourning. It does this to avoid accountability. Tacitly however, this is an admission of murder. Erasure is a confession. To stay with the obituary is to stay with the work of grieving and healing.

I have been spending hours reading obituaries lately. In my notebook against the names of dead strangers I write again and again and again and again- breath abbreviated.

Proposition Seven: A Century begins

Philosopher Peter Sloterdijk in his book Terror From the Air (2002) notes that the 20th century begins with a fundamental shift – from war to terrorism. He terms this ‘atmoterrorism’. Here it is no longer just the body of the enemy but the very atmospheric conditions of its survival that are poisoned. He locates 1915 as a landmark year which saw the first military use of chlorine, when an especially formed German ‘gas regiment’ attacked French and Canadian troops at Ypres by releasing 150 tons of this gas into the air (Sloterdijk, p. 10-12). Over a century later- there is still no antidote for chlorine exposure. The air however, has since been poisoned by more gases, multiple times by armies, corporations and militias- the enemy most often unsuspecting and vulnerable. The history of the 20th century is also a history of atmoterrorism.

Proposition Eight: Is Language Enough?

On the seventh day God breathed life into man’s nostrils to transform a form of clay into a living being. Several translators note how the Hebrew word for breathe / breathed could also imply a snuffing out of life. This dispute in language regarding the earliest reference to breathing is edifying. The Institute of Medical Humanities at Durham University has been investigating the ways the sensation of breathlessness often escapes language. Social location and access to resources also texture the differences in the way various people describe this sensation. Further the lag between clinical languages and those led by an embodied chaos, can help us come to terms with the unnarratability of even the most constituent parts of our being.

How is breathlessness afflicted by the entangled web of caste, nationality, religion, and structural hierarchies described? A complexity and intensity that is ungraspable in words. Can it be sensed and translated through the echoes held in the duration of breath?

Proposition Nine: Breathe In Breathe Out

“The Bhikkhu (Buddhist monk) trains thus: ‘Experiencing the mind, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Experiencing the mind, I will breathe out.’ He trains thus: ‘Gladdening the mind, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Gladdening the mind, I will breathe out.’ He trains thus: ‘Concentrating the mind, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Concentrating the mind, I will breathe out.’ He trains thus: ‘Liberating the mind, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Liberating the mind, I will breathe out.’ [The Patisambhida-magga says: “Intellect, intellection, heart, lucidity, mind, mind-base, mind-faculty, consciousness, consciousness aggregate, appropriate mind-consciousness element–that is mind.”] ‘He trains thus: ‘Contemplating impermanence, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating impermanence, I will breathe out.’ He trains thus: ‘Contemplating fading away, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating fading away, I will breathe out.’ He trains thus: ‘Contemplating cessation, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating cessation, I will breathe out.’ He trains thus: ‘Contemplating relinquishment, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating relinquishment, I will breathe out.

-Excerpt from Anapanasati Sutta, a discourse from the Buddha on breath and mind.

This is a visual meditation

on the psychic life of breath, a mindful contemplation of the sojourn through

medical, literary, political and artistic terrains. We stay with reverberations

from sound bowl healing practices, the sensation of breathing and letting go.

Without any text or spoken word- this section will be produced as an opening

into finding a restful and inquisitive breathing rhythm. This is in keeping

with Tibetan Buddhist practices where the lung ( rlung) is located not just in one place but in

various parts of the body (brain, thorax, heart, stomach, abdomen) and imagined

as a conductor of movement between mind, body and speech.

The future is not the beginning, but the forerunner, of a

new intense-formation.

The first time that you see me, you will see me, without implication of time.

The future expresses what is going to take place at some time to come, adding on the one hand an implication of will or intention, on the other hand of promise or threatening.

If you, villain, had not stopped [prāgrahīṣyaḥ] my mouth,

Without any implication of time.

Circles of future and desiderative border one another; the one sometimes expected

where the other might be met.

I, conditional, want you to stop my mouth; will you stop.

My mouth encircles the sustain of these refusals:

Sometimes and unexpected, unreasonable and polite.

If you, beautiful, would perceive this new stress-formation,

Reducing the noise of our [śyas] tomorrow,

Heads shaved, future universe, ‘victorious banners unlowered’.

Discipline of desire begins in the mouth.

– Nisha Ramayya, Joy of the Eyes

Hence breath

Then breath

Next breath

Subsequent breath

Because breath

Such breath

And breath

Same breath

Thereafter breath

Always breath

Thus breath

Perpetually breath

Yet breath

However breath

Therefore breath

In spite of breath

-Kim Hyesoon translated by Don Mee Choi – (excerpt from) Asphyxiation (Day Forty-Six)

Two iridescent alley flies

Circle the house until they die

Also confused

Proposition Ten: Repeat till your breath is full and drenched in these sounds.

: ‘Contemplating fading away, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating fading away, I will breathe out.’ He trains thus: ‘Contemplating cessation, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating cessation, I will breathe out.’ He trains thus: ‘Contemplating relinquishment, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating relinquishment, I will breathe out’.

: ‘Contemplating fading away, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating fading away, I will breathe out.’ He trains thus: ‘Contemplating cessation, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating cessation, I will breathe out.’ He trains thus: ‘Contemplating relinquishment, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating relinquishment, I will breathe out’.

: ‘Contemplating fading away, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating fading away, I will breathe out.’ He trains thus: ‘Contemplating cessation, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating cessation, I will breathe out.’ He trains thus: ‘Contemplating relinquishment, I will breathe in;’ he trains thus: ‘Contemplating relinquishment, I will breathe out’.

All images featured in the text are courtesy of the author unless stated otherwise.